AP European History

AP European History

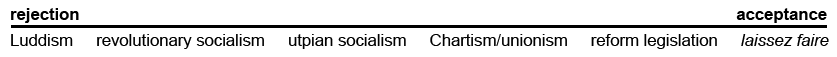

It is helpful to think of responses to these industrial problems on a continuum from acceptance of the new industrial system on one side to complete rejection on the other. We explore this topic further in the section below on “isms,” but for now focus on immediate and practical responses to those issues. You may find the following diagram helpful in imagining how these varying responses relate to one another.

We have already examined the laissez-faire approach of the classical economists. Many laypeople recognized the obvious problems with industrialization but believed that these side effects naturally attended all economic systems. To tamper with the workings of the free market, in their minds, would only create more suffering in the long run. Eventually the problems became too pronounced for any but the most hardened capitalist to ignore. Reformers feared that if nothing were done to ameliorate !:torrid working and living conditions, moral breakdown or, worse, revolution, would occur. In 1832; Parliament appointed the Sadler Commission to investigate child labor in mines and factories. The appalling testimony of workers convinced Parliament to pass the Factory Act of 1833, which provided for inspection of factories, a limitation on hours, and at least 2 hours of education per day for children. Sanitary reformer Edwin Chadwick’s (1800-1890) writings highlighted the need for improved sewage and sanitary conditions in the crowded and polluted cities. Soon after, the Parliament again responded with the Public Health Act of 1848, providing for the development of sanitary systems and public health boards to inspect conditions. Further acts are discussed below in the section “Reform in Great Britain.”

Despite the first tentative steps toward reform, workers voiced a more fundamental need for change, one that involved greater control over the workplace and political power. It became clear that, as individuals, workers could do little to blunt the capitalist system. To exert collective power, laborers formed unions. Skilled engineers formed a trade union, later called the Amalgamated Society of Engineers in 1851, to bargain for better working conditions and higher wages, much like medieval guilds. The more radical Grand National Consolidated Trade Union, encouraged by the industrialist Robert Owen (see below), attempted to organize all industrial workers for strikes and labor agitation. The British government looked with hostility on efforts at worker organization, passing the Combination Acts in the early 19th century to prevent union activity. Many workers favored more direct political activity. The Chartists, named after the founding document of their principles, employed petitions, mass meetings, and agitation to achieve universal male suffrage and the payment of salaries to members of Parliament. Chartism became associated with violent disturbances and faded as a movement after 1848, even though many of its goals were later reached.

Since socialism developed into a coherent ideology, it is covered more extensively in the section on “isms.” Luddism represented an outright rejection of the principle of mechanization of labor. Named for a mythical figure, Ned Ludd, the supporters of the movement met in secret throughout the early 1810s to plan the destruction of knitting frames and spinning devices they perceived as taking their skilled jobs. Many viewed the perpetuation of an artisanal culture of sturdy skilled craftsmen as preferable to any benefits from industrial efficiency. The British government crushed the movement by exiling or executing those involved. Today, those who oppose technological change are often dubbed by their detractors as Luddites.