For reference, click here for a map of The Lands Beyond

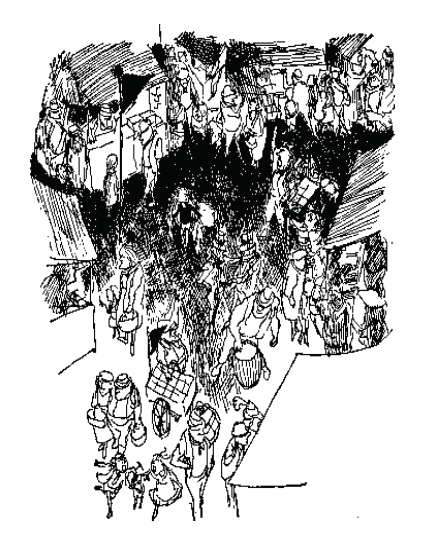

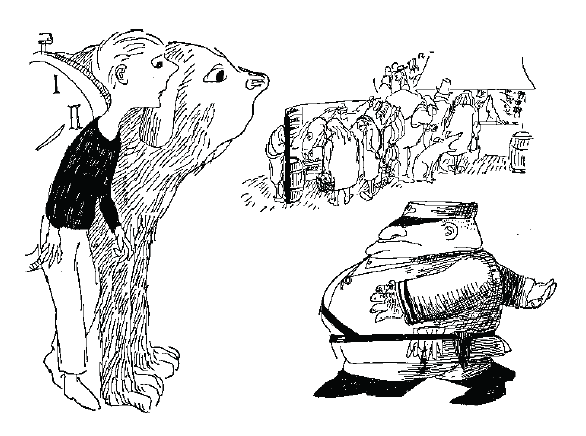

Indeed it was, for as they approached, Milo could see crowds of people pushing and shouting their way among the stalls, buying and selling, trading and bargaining. Huge wooden-wheeled carts streamed into the market square from the orchards, and long caravans bound for the four corners of the kingdom made ready to leave. Sacks and boxes were piled high waiting to be delivered to the ships that sailed the Sea of Knowledge, and off to one side a group of minstrels sang songs to the delight of those either too young or too old to engage in trade. But above all the noise and tumult of the crowd could be heard the merchants’ voices loudly advertising their products.

“Get your fresh-picked ifs, ands, and buts.”

“Hey-yaa, hey-yaa, hey-yaa, nice ripe wheres and whens.”

“Juicy, tempting words for sale.”

So many words and so many people! They were from every place imaginable and some places even beyond that, and they were all busy sorting, choosing, and stuffing things into cases. As soon as one was filled, another was begun. There seemed to be no end to the bustle and activity.

Milo and Tock wandered up and down the aisles looking at the wonderful assortment of words for sale. There were short ones and easy ones for everyday use, and long and very important ones for special occasions, and even some marvelously fancy ones packed in individual gift boxes for use in royal decrees and pronouncements.

“Step right up, step right up – fancy, best-quality words right here,” announced one man in a booming voice. “Step right up – ah, what can I do for you, little boy? How about a nice bagful of pronouns – or maybe you’d like our special assortment of names?”

Milo had never thought much about words before, but these looked so good that he longed to have some.

“Look, Tock,” he cried, “aren’t they wonderful?”

“They’re fine, if you have something to say,” replied Tock in a tired voice, for he was much more interested in finding a bone than in shopping for new words.

“Maybe if I buy some I can learn how to use them,” said Milo eagerly as he began to pick through the words in the stall. Finally he chose three which looked particularly good to him – “quagmire,” “flabbergast,” and “upholstery.” He had no idea what they meant, but they looked very grand and elegant.

“How much are these?” he inquired, and when the man whispered the answer he quickly put them back on the shelf and started to walk on.

“Why not take a few pounds of ‘happys’?” advised the salesman. “They’re much more practical – and very useful for Happy Birthday, Happy New Year, happy days, and happy-go-lucky.”

“I’d like to very much,” began Milo, “but…”

“Or perhaps you’d be interested in a package of ‘goods’ – always handy for good morning, good afternoon, good evening, and good-by,” he suggested.

Milo did want to buy something, but the only money he had was the coin he needed to get back through the tollbooth, and Tock, of course, had nothing but the time.

“No, thank you,” replied Milo. “We’re just looking.”

And they continued on through the market. “As they turned down the last aisle of stalls, Milo noticed a wagon that seemed different from the rest. On its side was a small neatly lettered sign that said “DO IT YOURSELF,” and inside were twenty-six bins filled with all the letters of the alphabet from A to Z.

“These are for people who like to make their own words,” the man in charge informed him. “You can pick any assortment you like or buy a special box complete with all letters, punctuation marks, and a book of instructions. Here, taste an A; they’re very good.”

Milo nibbled carefully at the letter and discovered that it was quite sweet and delicious – just the way you’d expect an A to taste.

“I knew you’d like it,” laughed the letter man, popping two G’s and an R into his mouth and letting the juice drip down his chin. “A’s are one of our most popular letters. All of them aren’t that good,” he confided in a low voice. “Take the Z, for instance – very dry and sawdusty. And the X? Why, it tastes like a trunkful of stale air. That’s why people hardly ever use them. But most of the others are quite tasty. Try some more.”

He gave Milo an I, which was icy and refreshing, and Tock a crisp, crunchy C.

“Most people are just too lazy to make their own words,” he continued, “but it’s much more fun.”

“Is it difficult? I’m not much good at making words,” admitted Milo, spitting the pits from a P.

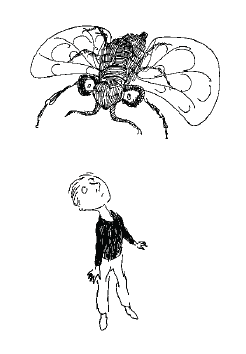

“Perhaps I can be of some assistance – a-s-s-i-s-t-a-n-c-e,” buzzed an unfamiliar voice, and when Milo looked up he saw an enormous bee, at least twice his size, sitting on top of the wagon.

“I am the Spelling Bee,” announced the Spelling Bee. “Don’t be alarmed – a-l-a-r-m-e-d.”

Tock ducked under the wagon, and Milo, who was not overly fond of normal-sized bees, began to back away slowly.

“I can spell anything – a-n-y-t-h-i-n-g,” he boasted, testing his wings. “Try me, try me!”

“Can you spell good-by?” suggested Milo as he continued to back away.

The bee gently lifted himself into the air and circled lazily over Milo’s head.

“Perhaps – p-e-r-h-a-p-s – you are under the misapprehension – m-i-s-a-p-p-r-e-h-e-n-s-i-o-n – that I am dangerous,” he said, turning a smart loop to the left. “Let me assure – a-s-s-u-r-e – you that my intentions are peaceful – p-e-a-c-e-f-u-l.” And with that he settled back on top of the wagon and fanned himself with one wing. “Now,” he panted, “think of the most difficult word you can and I’ll spell it. Hurry up, hurry up!” And he jumped up and down impatiently.

“He looks friendly enough,” thought Milo, not sure just how friendly a friendly bumblebee should be, and tried to think of a very difficult word.

“Spell Vegetable,’ “he suggested, for it was one that always troubled him at school.

“That is a difficult one,” said the bee, winking at the letter man. “Let me see now . . . hmmmmmm . . .” He frowned and wiped his brow and paced slowly back and forth on top of the wagon. “How much time do I have?”

“Just ten seconds,” cried Milo excitedly. “Count them off, Tock.”

“Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear, oh dear,” the bee repeated, continuing to pace nervously. Then, just as the time ran out, he spelled as fast as he could – “v-e-g-e-t-a-b-l-e.”

“Correct,” shouted the letter man, and everyone cheered.

“Can you spell everything?” asked Milo admiringly.

“Just about,” replied the bee with a hint of pride in his voice. “You see, years ago I was just an ordinary bee minding my own business, smelling flowers all day, and occasionally picking up part-time work in people’s bonnets. Then one day I realized that I’d never amount to anything without an education and, being naturally adept at spelling, I decided that “

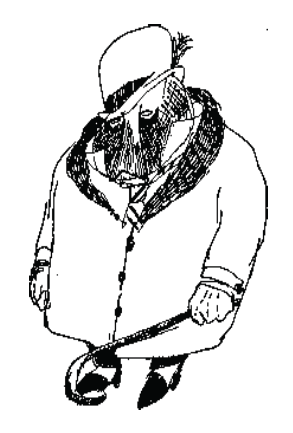

“BALDERDASH!” shouted a booming voice. And from around the wagon stepped a large beetlelike insect dressed in a lavish coat, striped pants, checked vest, spats, and a derby hat. “Let me repeat – BALDERDASH!” he shouted again, swinging his cane and clicking his heels in midair. “Come now, don’t be ill-mannered. Isn’t someone going to introduce me to the little boy?”

“This,” said the bee with complete disdain, “is the Humbug. A very dislikable fellow.”

“NONSENSE! Everyone loves a Humbug,” shouted the Humbug. “As I was saying to the king just the other day – – “

“You’ve never met the king,” accused the bee angrily. Then, turning to Milo, he said, “Don’t believe a thing this old fraud says.”

“BOSH!” replied the Humbug. “We’re an old and noble family, honorable to the core – Insertions Humbugium,if I may use the Latin. Why, we fought in the crusades with Richard the Lion Heart, crossed the Atlantic with Columbus, blazed trails with the pioneers, and today many members of the family hold prominent government positions throughout the world. History is full of Humbugs.”

“A very pretty speech – s-p-e-e-c-h,” sneered the bee. “Now why don’t you go away? I was just advising the lad of the importance of proper spelling.”

“BAH!” said the bug, putting an arm around Milo. “As soon as you learn to spell one word, they ask you to spell another. You can never catch up – so why bother? Take my advice, my boy, and forget about it. As my great-great-great-grandfather George Washington Humbug used to say…”

“You, sir,” shouted the bee very excitedly, “are an impostor – i-m-p-o-s-t-o-r – who can’t even spell his own name.”

“A slavish concern for the composition of words is the sign of a bankrupt intellect,” roared the Humbug, waving his cane furiously.

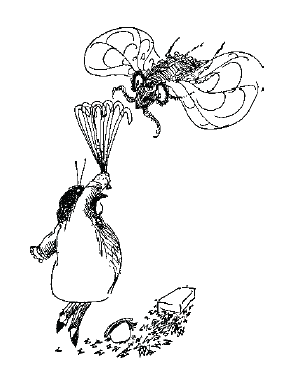

Milo didn’t have any idea what this meant, but it seemed to infuriate the Spelling Bee, who flew down and knocked off the Humbug’s hat with his wing.

“Be careful,” shouted Milo as the bug swung his cane again, catching the bee on the foot and knocking over the box of W’s.

“My foot!” shouted the bee.

“My hat!” shouted the bug – and the fight was on.

The Spelling Bee buzzed dangerously in and out of range of the Humbug’s wildly swinging cane as they menaced and threatened each other, and the crowd stepped back out of danger.

“There must be some other way to…” began Milo. And then he yelled, “WATCH OUT,” but it was too late. There was a tremendous crash as the Humbug in his great fury tripped into one of the stalls, knocking it into another, then another, then another, then another, until every stall in the market place had been upset and the words lay scrambled in great confusion all over the square.

The bee, who had tangled himself in some bunting, toppled to the ground, knocking Milo over on top of him, and lay there shouting, “Help! Help! There’s a little boy on me.” The bug sprawled untidily on a mound of squashed letters and Tock, his alarm ringing persistently, was buried under a pile of words.

“Done what you’ve looked,” angrily shouted one of the salesmen. He meant to say “Look what you’ve done,” but the words had gotten so hopelessly mixed up that no one could make any sense at all.

“Do going to we what are!” complained another, as everyone set about straightening things up as well as they could.

For several minutes no one spoke an understandable sentence, which added greatly to the confusion. As soon as possible, however, the stalls were righted and the words swept into one large pile for sorting. The Spelling Bee, who was quite upset by the whole affair, had flown off in a huff, and just as Milo got to his feet the entire police force of Dictionopolis appeared – loudly blowing his whistle.

“Now we’ll get to the bottom of this,” he heard someone say. “Here comes Officer Shrift.”

Striding across the square was the shortest policeman Milo had ever seen. He was scarcely two feet tall and almost twice as wide, and he wore a blue uniform with white belt and gloves, a peaked cap, and a very fierce expression.

He continued blowing the whistle until his face was beet red, stopping only long enough to shout, “You’re guilty, you’re guilty,” at everyone he passed. “I’ve never seen anyone so guilty,” he said as he reached Milo. Then, turning towards Tock, who was still ringing loudly, he said, “Turn off that dog; it’s disrespectful to sound your alarm in the presence of a policeman.”

He made a careful note of that in his black book and strode up and down, his hands clasped behind his back, surveying the wreckage in the market place.

“Very pretty, very pretty.” He scowled. “Who’s responsible for all this? Speak up or I’ll arrest the lot of you.”

There was a long silence. Since hardly anybody had actually seen what had happened, no one spoke.

“You,” said the policeman, pointing an accusing finger at the Humbug, who was brushing himself off and straightening his hat, “you look suspicious to me.”

The startled Humbug dropped his cane and nervously replied, “Let me assure you, sir, on my honor as a gentleman, that I was merely an innocent bystander, minding my own business, enjoying the stimulating sights and sounds of the world of commerce, when this young lad “

“AHA!” interrupted Officer Shrift, making another note in his little book. “Just as I thought: boys are the cause of everything.”

“Pardon me,” insisted the Humbug, “but I in no way meant to imply that “

“SILENCE!” thundered the policeman, pulling himself up to full height and glaring menacingly at the terrified bug. “And now,” he continued, speaking to Milo, “where were you on the night of July 27?”

“What does that have to do with it?” asked Milo.

“It’s my birthday, that’s what,” said the policeman as he entered “Forgot my birthday” in his little book “Boys always forget other people’s birthdays.

“You have committed the following crimes,” he continued: “having a dog with an unauthorized alarm, sowing confusion, upsetting the applecart, wreaking havoc, and mincing words.”

“Now see here,” growled Tock angrily.

“And illegal barking,” he added, frowning at the watchdog. “It’s against the law to bark without using the barking meter. Are you ready to be sentenced?”

“Only a judge can sentence you,” said Milo, who remembered reading that in one of his schoolbooks.

“Good point,” replied the policeman, taking off his cap and putting on a long black robe. “I am also the judge. Now would you like a long or a short sentence?”

“A short one, if you please,” said Milo.

“Good,” said the judge, rapping his gavel three times. “I always have trouble remembering the long ones. How about ‘I am’? That’s the shortest sentence I know.”

Everyone agreed that it was a very fair sentence, and the judge continued: “There will also be a small additional penalty of six million years in prison. Case closed,” he pronounced, rapping his gavel again. “Come with me. I’ll take you to the dungeon.”

“Only a jailer can put you in prison,” offered Milo, quoting the same book.

“Good point,” said the judge, removing his robe and taking out a large bunch of keys. “I am also the jailer.”

And with that he led them away.

“Keep your chin up,” shouted the Humbug. “Maybe they’ll take a million years off for good behavior.”

The heavy prison door swung back slowly and Milo and Tock followed Officer Shrift down a long dark corridor lit by only an occasional flickering candle.

“Watch the steps,” advised the policeman as they started down a steep circular staircase. The air was dank and musty – like the smell of wet blankets – and the massive stone walls were slimy to the touch. Down and down they went until they arrived at another door even heavier and stronger-looking than the first. A cobweb brushed across Milo’s face and he shuddered.

“You’ll find it quite pleasant here,” chuckled the policeman as he slid the bolt back and pushed the door open with a screech and a squeak. “Not much company, but you can always chat with the witch.”

“The witch?” trembled Milo.

“Yes, she’s been here for a long time,” he said, starting along another corridor.

In a few more minutes they had gone through three other doors, across a narrow footbridge, down two more corridors and another stairway, and stood finally in front of a small cell door.

“This is it,” said the policeman. “All the comforts of home.”

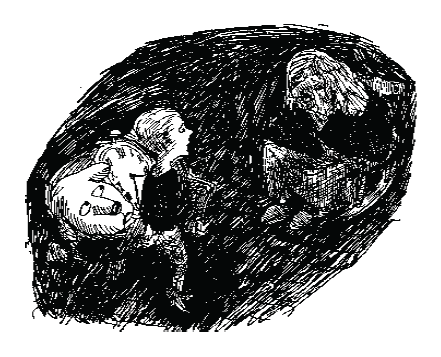

The door opened and then shut and Milo and Tock found themselves in a high vaulted cell with two tiny windows halfway up on the wall.

“See you in six million years,” said Officer Shrift, and the sound of his foot-steps grew fainter and fainter until it wasn’t heard at all.

“It looks serious, doesn’t it, Tock?” said Milo very sadly.

“It certainly does,” the dog replied, sniffing around to see what their new quarters were like.

“I don’t know what we’re going to do for all that time; we don’t even have a checker set or a box of crayons.”

“Don’t worry,” growled Tock, raising one paw assuringly, “something will turn up. Here, wind me, will you please? I’m beginning to run down.”

“You know something, Tock?” he said as he wound up the dog. “You can get in a lot of trouble mixing up words or just not knowing how to spell them. If we ever get out of here, I’m going to make sure to learn all about them.”

“A very commendable ambition, young man,” said a small voice from across the cell.

Milo looked up, very surprised, and noticed for the first time, in the half-light of the room, a pleasant-looking old lady quietly knitting and rocking.

“Hello,” he said.

“How do you do?” she replied.

“You’d better be very careful,” Milo advised. “I understand there’s a witch somewhere in here.”

“I am she,” the old lady answered casually, and pulled her shawl a little closer around her shoulders.

Milo jumped back in fright and quickly grabbed Tock to make sure that his alarm didn’t go off – for he knew how much witches hate loud noises.

“Don’t be frightened,” she laughed. “I’m not a witch – I’m a Which.”

“Oh,” said Milo, because he couldn’t think of anything else to say.

“I’m Faintly Macabre, the not-so-wicked Which,” she continued, “and I’m certainly not going to harm you.”

“What’s a Which?” asked Milo, releasing Tock and stepping a little closer.

“Well,” said the old lady, just as a rat scurried across her foot, “I am the king’s great aunt. For years and years I was in charge of choosing which words were to be used for all occasions, which ones to say and which ones not to say, which ones to write and which ones not to write. As you can well imagine, with all the thousands to choose from, it was a most important and responsible job. I was given the title of ‘Official Which,’ which made me very proud and happy.

“At first I did my best to make sure that only the most proper and fitting words were used. Everything was said clearly and simply and no words were wasted. I had signs posted all over the palace and market place which said:

Brevity is the Soul of Wit.

“But power corrupts, and soon I grew miserly and chose fewer and fewer words, trying to keep as many as possible for myself. I had new signs posted which said:

An Ill-chosen Word is the Fool’s Messenger

“Soon sales began to fall off in the market. The people were afraid to buy as many words as before, and hard times came to the kingdom. But still I grew more and more miserly. Soon there were so few words chosen that hardly anything could be said, and even casual conversation became difficult. Again I had new signs posted, which said:

Speak Fitly or be Silent Wisely.

“And finally I had even these replaced by ones which read simply:

Silence is Golden.

“All talk stopped. No words were sold, the market place closed down, and the people grew poor and disconsolate. When the king saw what had happened, he became furious and had me cast into this dungeon where you see me now, an older and wiser woman.

“That was all many years ago,” she continued; “but they never appointed a new Which, and that explains why today people use as many words as they can and think themselves very wise for doing so. For always remember that while it is wrong to use too few, it is often far worse to use too many.”

When she had finished, she sighed deeply, patted Milo gently on the shoulder, and began knitting once again.

“And have you been down here ever since then?” asked Milo sympathetically.’

“Yes,” she said sadly. “Most people have forgotten me entirely, or remember me wrongly as a witch not a Which. But it matters not, it matters not,” she went on unhappily, “for they are equally frightened of both.”

“I don’t think you’re frightening,” said Milo, and Tock wagged his tail in agreement.

“I thank you very much,” said Faintly Macabre. “You may call me Aunt Faintly. Here, have a punctuation mark.” And she held out a box of sugar-coated question marks, periods, commas, and exclamation points. “That’s all I get to eat now.”

“Well, when I get out of here, I’m going to help you,” Milo declared forcefully.

“That’s very nice of you,” she replied; “but the only thing that can help me is the return of Rhyme and Reason.”

“The return of what?” asked Milo.

“Rhyme and Reason,” she repeated; “but that’s another long story, and you may not want to hear it.”

“We would like to very much,” barked Tock.

“We really would,” agreed Milo, and as the Which rocked slowly back and forth she told them this story.

“Once upon a time, this land was a barren and frightening wilderness whose high rocky mountains sheltered the evil winds and whose barren valleys offered hospitality to no man. Few things grew, and those that did were bent and twisted and their fruit was as bitter as wormwood. What wasn’t waste was desert, and what wasn’t desert was rock, and the demons of darkness made their home in the hills. Evil creatures roamed at will through the countryside and down to the sea. It was known as the land of Null.

“Then one day a small ship appeared on the Sea of Knowledge. It carried a young prince seeking the future. In the name of goodness and truth he laid claim to all the country and set out to explore his new domain. The demons, monsters, and giants were furious at his presumption and banded together to drive him out. The earth shook with their battle, and when they had finished, all that remained to the prince was a small piece of land at the edge of the sea.

“ ‘I’ll build my city here,’ he declared, and that is what he did.

“Before long, more ships came bearing settlers for the new land and the city grew and pushed its boundaries farther and farther out. Each day it was attacked anew, but nothing could destroy the prince’s new city. And grow it did. Soon it was no longer just a city; it was a kingdom, and it was called the kingdom of Wisdom.

“But, outside the walls, all was not safe, and the new king vowed to conquer the land that was rightfully his. So each spring he set forth with his army and each autumn he returned, and year by year the kingdom grew larger and more prosperous. He took to himself a wife and before long had two fine young sons to whom he taught everything he knew so that one day they might rule wisely.

“When the boys grew to young-manhood, the king called them to him and said: ‘I am becoming an old man and can no longer go forth to battle. You must take my place and found new cities in the wilderness, for the kingdom of Wisdom must grow.’

“And so they did. One went south to the Foothills of Confusion and built Dictionopolis, the city of words; and one went north to the Mountains of Ignorance and built Digitopolis, the city of numbers. Both cities flourished mightily and the demons were driven back still further. Soon other cities and towns were founded in the new lands, and at last only the farthest reaches of the wilderness remained to these terrible creatures – and there they waited, ready to strike down all who ventured near or relaxed their guard.

“The two brothers were glad, however, to go their separate ways, for they were by nature very suspicious and jealous. Each one tried to outdo the other, and they worked so hard and diligently at it that before long their cities rivaled even Wisdom in size and grandeur.

“ ‘Words are more important than wisdom,’ said one privately.

“ ‘Numbers are more important than wisdom,’ thought the other to himself.

“And they grew to dislike each other more and more.

“The old king, however, who knew nothing of his sons’ animosity, was very happy in the twilight of his reign and spent his days quietly walking and contemplating in the royal gardens. His only regret was that he’d never had a daughter, for he loved little girls as much as he loved little boys. One day as he was strolling peacefully about the grounds, he discovered two tiny babies that had been abandoned in a basket under the grape arbor. They were beautiful golden-haired girls.

“The king was overjoyed. ‘They have been sent to crown my old age,’ he cried, and called the queen, his ministers, the palace staff, and, indeed, the entire population to see them.

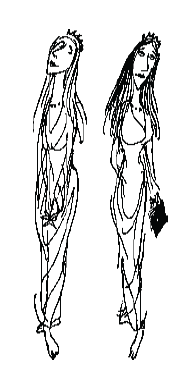

“ ‘We’ll call this one Rhyme and this one Reason,’ he said, and so they became the Princess of Sweet Rhyme and the Princess of Pure Reason and were brought up in the palace.

“When the old king finally died, the kingdom was divided between his two sons, with the provision that they would be equally responsible for the welfare of the young princesses. One son went south and became Azaz, the unabridged king of Dictionopolis, and the other went” north and became the Mathemagician, ruler of Digitopolis; and, true to their words, they both provided well for the little girls, who continued to live in Wisdom.

“Everyone loved the princesses because of their great beauty, their gentle ways, and their ability to settle all controversies fairly and reasonably. People with problems or grievances or arguments came from all over the land to seek advice, and even the two brothers, who by this time were fighting continuously, often called upon them to help decide matters of state. It was said by everyone that ‘Rhyme and Reason answer all problems.’

“As the years passed, the two brothers grew farther and farther apart and their separate kingdoms became richer and grander. Their disputes, however, became more and more difficult to reconcile. But always, with patience and love, the princesses set things right.

“Then one day they had the most terrible quarrel of all. King Azaz insisted that words were far more significant than numbers and hence his kingdom was truly the greater and the Mathemagician claimed that numbers were much more important than words and hence his kingdom was supreme. They discussed and debated and raved and ranted until they were on the verge of blows, when it was decided to submit the question to arbitration by the princesses.

“After days of careful consideration, in which all the evidence was weighed and all the witnesses heard, they made their decision:

“ ‘Words and numbers are of equal value, for, in the cloak of knowledge, one is warp and the other woof. It is no more important to count the sands than it is to name the stars. Therefore, let both kingdoms live in peace.’

“Everyone was pleased with the verdict. Everyone, that is, but the brothers, who were beside themselves with anger.

“ ‘What good are these girls if they cannot settle an argument in someone’s favor?’ they growled, since both were more interested in their own advantage than in the truth. ‘We’ll banish them from the kingdom forever.’

“And so they were taken from the palace and sent far away to the Castle in the Air, and they have not been seen since. That is why today, in all this land, there is neither Rhyme nor Reason.”

“And what happened to the two rulers?” asked Milo.

“Banishing the two princesses was the last thing they ever agreed upon, and they soon fell to warring with each other. Despite this, their own kingdoms have continued to prosper, but the old city of Wisdom has fallen into great disrepair, and there is no one to set things right. So, you see, until the princesses return, I shall have to stay here.”

“Maybe we can rescue them,” said Milo as he saw how sad the Which looked.

“Ah, that would be difficult,” she replied. “The Castle in the Air is far from here, and the one stairway which leads to it is guarded by fierce and black-hearted demons.”

Tock growled ominously, for he hated even the thought of demons.

“I’m afraid there’s not much a little boy and a dog can do,” she said, “but never you mind; it’s not so bad. I’ve grown quite used to it here. But you must be going or else you’ll waste the whole day.”

“Oh, we’re here for six million years,” sighed Milo, “and I don’t see any way to escape.”

“Nonsense,” scolded the Which, “you mustn’t take Officer Shrift so seriously. He loves to put people in prison, but he doesn’t care about keeping them there. Now just press that button in the wall and be on your way.”

Milo pressed the button and a door swung open, letting in a shaft of brilliant sunshine.

“Good-by; come again,” shouted the Which as they stepped outside and the door slammed shut.

Milo and Tock stood blinking in the bright light and, as their eyes became accustomed to it, the first things they saw were the king’s advisers again rushing toward them.

“Ah, there you are.”

“Where have you been?”

“We’ve been looking all over for you.”

“The Royal Banquet is about to begin.”

“Come with us.”

They seemed very agitated and out of breath as Milo walked along with them.

“But what about my car?” he asked.

“Don’t need it,” replied the duke.

“No use for it,” said the minister.

“Superfluous,” advised the count.

“Unnecessary,” stated the earl.

“Uncalled for,” cried the undersecretary. “We’ll take our vehicle.”

“Conveyance.”

“Rig.”

“Charabanc.”

“Chariot.”

“Buggy.”

“Coach.”

“Brougham.”

“Shandrydan,” they repeated quickly in order, and pointed to a small wooden wagon.

“Oh dear, all those words again,” thought Milo as he climbed into the wagon with Tock and the cabinet members.

“How are you going to make it move? It doesn’t have a…”

“Be very quiet,” advised the duke, “for it goes without saying.”

And, sure enough, as soon as they were all quite still, it began to move quickly through the streets, and in a very short time they arrived at the royal palace.

“Right this way.”

“Follow us.”

“Come along.”

“Step lively.”

“Here we go,” they shouted, hopping from the wagon and bounding up the broad marble stairway. Milo and Tock followed close behind. It was a strange-looking palace, and if he didn’t know better he would have said that it looked exactly like an enormous book, standing on end, with its front door in the lower part of the binding just where they usually place the publisher’s name.

Once inside, they hurried down a long hallway, which glittered with crystal chandeliers and echoed with their footsteps. The walls and ceiling were covered with mirrors, whose reflections danced dizzily along with them, and the footmen bowed coldly.

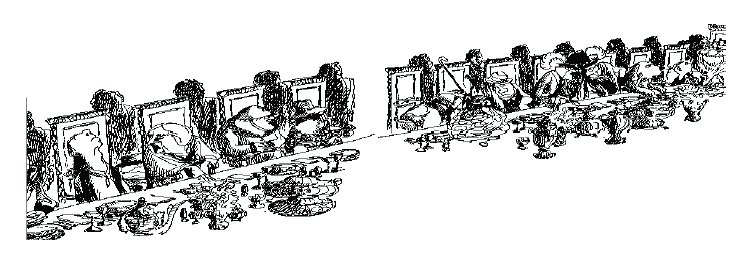

“We must be terribly late,” gasped the earl nervously as they reached the tall doors of the banquet hall. It was a vast room, full of people loudly talking and arguing. The long table was carefully set with gold plates and linen napkins. An attendant stood behind each chair, and at the center, raised slightly above the others, was a throne covered in crimson cloth. Directly behind, on the wall, was the royal coat of arms, flanked by the flags of Dictionopolis.

Milo noticed many of the people he had seen in the market place. The letter man was busy explaining to an interested group the history of the W, and off in a corner the Humbug and the Spelling Bee were arguing fiercely about nothing at all. Officer Shrift wandered through the crowd, suspiciously muttering, “Guilty, guilty, they’re all guilty,” and, on noticing Milo, brightened visibly and commented in passing, “Is it six million years already? My, how time flies.”

Everyone seemed quite grumpy about having to wait for lunch, and they were all relieved to see the tardy guests arrive.

“Certainly glad you finally made it, old man,” said the Humbug, cordially pumping Milo’s hand. “As guest of honor you must choose the menu of course.”

“Oh, my,” he thought, not knowing what to say.

“Be quick about it,” suggested the Spelling Bee. “I’m famished – f-a-m-i-s-h-e-d.”

As Milo tried to think, there was an ear-shattering blast of trumpets, entirely off key, and a page announced to the startled guests:

“KING AZAZ THE UNABRIDGED.”

The king strode through the door and over to the table and settled his great bulk onto the throne, calling irritably, “Places, everyone. Take your places.” He was the largest man Milo had ever seen, with a great stomach, large piercing eyes, a gray beard that reached to his waist, and a silver signet ring on the little finger of his left hand. He also wore a small crown and a robe with the letters of the alphabet beautifully embroidered all over it.

“What have we here?” he said, staring down at Tock and Milo as everyone else took his place.

“If you please,” said Milo, “my name is Milo and this is Tock. Thank you very much for inviting us to your banquet, and I think your palace is beautiful.”

“Exquisite,” corrected the duke.

“Lovely,” counseled the minister.

“Handsome,” recommended the count.

“Pretty,” hinted the Earl.

“Charming,” submitted the undersecretary.

“SILENCE,” suggested the king. “Now, young man, what can you do to entertain us? Sing songs? Tell stories? Compose sonnets? Juggle plates? Do tumbling tricks? Which is it?”

“I can’t do any of those things,” admitted Milo.

“What an ordinary little boy,” commented the king. “Why, my cabinet members can do all sorts of things. The duke here can make mountains out of molehills. The minister splits hairs. The count makes hay while the sun shines. The earl leaves no stone unturned. And the undersecretary,” he finished ominously, “hangs by a thread. Can’t you do anything at all?”

“I can count to a thousand,” offered Milo.

“A-A-R-G-H, numbers! Never mention numbers here. Only use them when we absolutely have to,” growled Azaz disgustedly. “Now, why don’t you and Tock come up here and sit next to me, and we’ll have some dinner?”

“Are you ready with the menu?” reminded the Humbug.

“Well,” said Milo, remembering that his mother had always told him to eat lightly when he was a guest, “why don’t we have a light meal?”

“A light meal it shall be,” roared the bug, waving his arms.

The waiters rushed in carrying large serving platters and set them on the table in front of the king. When he lifted the covers, shafts of brilliant-colored light leaped from the plates and bounced around the ceiling, the walls, across the floor, and out the windows.

“Not a very substantial meal,” said the Humbug, rubbing his eyes, “but quite an attractive one. Perhaps you can suggest something a little more filling.”

The king clapped his hands, the platters were removed, and, without thinking, Milo quickly suggested, “Well, in that case, I think we ought to have a square meal of…”

“A square meal it is,” shouted the Humbug again.

The king clapped his hands once more and the waiters reappeared carrying plates heaped high with steaming squares of all sizes and colors.

“Ugh,” said the Spelling Bee, tasting one, “these are awful.”

No one else seemed to like them very much either, and the Humbug got one caught in his throat and almost choked.

“Time for the speeches,” announced the king as the plates were again removed and everyone looked glum.

“You first,” he commanded, pointing to Milo.

“Your Majesty, ladies and gentlemen,” started Milo timidly, “I would like to take this opportunity to say that in all the “

“That’s quite enough,” snapped the king. “Mustn’t talk all day.”

“But I’d just begun,” objected Milo.

“NEXT!” bellowed the king.

“Roast turkey, mashed potatoes, vanilla ice cream,” recited the Humbug, bouncing up and down quickly.

“What a strange speech,” thought Milo, for he’d heard many in the past and knew that they were supposed to be long and dull.

“Hamburgers, corn on the cob, chocolate pudding – p-u-d-d-i-n-g,” said the Spelling Bee in his turn.

“Frankfurters, sour pickles, strawberry jam,” shouted Officer Shrift from his chair. Since he was taller sitting than standing, he didn’t bother to get up.

And so down the line it went, with each guest rising briefly, making a short speech, and then resuming his place. When everyone had finished, the king rose.

“Pate de foie gras, soupe a l’oignon, faisan sous cloche, salade endive, fromages et fruits et demi-tasse,” he said carefully and clapped his hands again.

The waiters reappeared immediately, carrying heavy, hot trays, which they set on the table. Each one contained the exact words spoken by the various guests, and they all began eating immediately with great gusto.

“Dig in,” said the king, poking Milo with his elbow and looking disapprovingly at his plate. “I can’t say that I think much of your choice.”

“I didn’t know that I was going to have to eat my words,” objected Milo.

“Of course, of course, everyone here does,” the king grunted. “You should have made a tastier speech.”

Milo looked around at everyone busily stuffing himself and then back at his own unappetizing plate. It certainly didn’t look worth eating, and he was so very hungry.

“Here, try some somersault,” suggested the duke. “It improves the flavor.”

“Have a rigmarole,” offered the count, passing the breadbasket.

“Or a ragamuffin,” seconded the minister.

“Perhaps you’d care for a synonym bun,” suggested the duke.

“Why not wait for your just desserts?” mumbled the earl indistinctly, his mouth full of food.

“How many times must I tell you not to bite off more than you can chew?” snapped the undersecretary, patting the distressed earl on the back.

“In one ear and out the other,” scolded the duke, attempting to stuff one of his words through the earl’s head.

“If it isn’t one thing, it’s another,” chided the minister.

“Out of the frying pan into the fire,” shouted the count, burning himself badly.

“Well, you don’t have to bite my head off,” screamed the terrified earl, and flew at the others in a rage.

The five of them scuffled wildly under the table.

“STOP THAT AT ONCE,” thundered Azaz, “or I’ll banish the lot of you!”

“Sorry.”

“Excuse me.”

“Forgive us.”

“Pardon.”

“Regrets,” they apologized in turn, and sat down glaring at each other.

The rest of the meal was finished in silence until the king, wiping the gravy stains from his vest, called for dessert. Milo, who had not eaten anything, looked up eagerly.

“We’re having a special treat today,” said the king as the delicious smells of homemade pastry filled the banquet hall. “By royal command the pastry chefs have worked all night in the half bakery to make sure that “

“The half bakery?” questioned Milo.

“Of course, the half bakery,” snapped the king. “Where do you think half-baked ideas come from? Now, please don’t interrupt. By royal command the pastry chefs have worked all night to…”

“What’s a half-baked idea?” asked Milo again.

“Will you be quiet?” growled Azaz angrily; but, before he could begin again, three large serving carts were wheeled into the hall and everyone jumped up to help himself.

“They’re very tasty,” explained the Humbug, “but they don’t always agree with you. Here’s one that’s very good.” He handed it to Milo and, through the icing and nuts, Milo saw that it said “THE EARTH IS FLAT.”

“People swallowed that one for years,” commented the Spelling Bee, “but it’s not very popular these days – d-a-y-s.” He picked up a long one that stated “THE MOON IS MADE OF GREEN CHEESE” and hungrily bit off the part that said “CHEESE.” “Now there’s a half-baked idea,” he said, smiling.

Milo looked at the great assortment of cakes, which were being eaten almost as quickly as anyone could read them. The count was munching contentedly on “IT NEVER RAINS BUT IT POURS” and the king was busy slicing one that stated “NIGHT AIR IS BAD AIR.”

“I wouldn’t eat too many of those if I were you,” advised Tock. “They may look good, but you can get terribly sick of them.”

“Don’t worry,” Milo replied; “I’ll just wrap one up for later,” and he folded his napkin around “EVERYTHING HAPPENS FOR THE BEST.”