For reference, click here for a map of The Lands Beyond

The Humbug whistled gaily at his work, for he was never as happy as when he had a job which required no thinking at all. After what seemed like days, he had dug a hole scarcely large enough for his thumb. Tock shuffled steadily back and forth with the dropper in his teeth, but the full well was still almost as full as when he began, and Milo’s new pile of sand was hardly a pile at all.

“How very strange,” said Milo, without stopping for a moment. “I’ve been working steadily all this time, and I don’t feel the slightest bit tired or hungry. I could go right on the same way forever.”

“Perhaps you will,” the man agreed with a yawn (at least it sounded like a yawn).

“Well, I wish I knew how long it was going to take,” Milo whispered as the dog went by again.

“Why not use your magic staff and find out?” replied Tock as clearly as anyone could with an eye dropper in his mouth.

Milo took the shiny pencil from his pocket and quickly calculated that, at the rate they were working, it would take each of them eight hundred and thirty-seven years to finish.

“Pardon me,” he said, tugging at the man’s sleeve and holding the sheet of figures up for him to see, “but it’s going to take eight hundred and thirty-seven years to do these jobs.”

“Is that so?” replied the man, without even turning around. “Well, you’d better get on with it then.”

“But it hardly seems worth while,” said Milo softly.

“WORTH WHILE!” the man roared indignantly.

“All I meant was that perhaps it isn’t too important,” Milo repeated, trying not to be impolite.

“Of course it’s not important,” he snarled angrily. “I wouldn’t have asked you to do it if I thought it was important.” And now, as he turned to face them, he didn’t seem quite so pleasant.

“Then why bother?” asked Tock, whose alarm suddenly began to ring.

“Because, my young friends,” he muttered sourly, “what could be more important than doing unimportant things? If you stop to do enough of them, you’ll never get to where you’re going.” He punctuated his last remark with a villainous laugh.

“Then you must “ gasped Milo.

“Quite correct!” he shrieked triumphantly. “I am the Terrible Trivium, demon of petty tasks and worthless jobs, ogre of wasted effort, and monster of habit.”

The Humbug dropped his needle and stared in disbelief while Milo and Tock began to back away slowly.

“Don’t try to leave,” he ordered, with a menacing sweep of his arm, “for there’s so very much to do, and you still have over eight hundred years to go on the first job.”

“But why do only unimportant things?” asked Milo, who suddenly remembered how much time he spent each day doing them.

“Think of all the trouble it saves,” the man explained, and his face looked as if he’d be grinning an evil grin – if he could grin at all. “If you only do the easy and useless jobs, you’ll never have to worry about the important ones which are so difficult. You just won’t have the time. For there’s always something to do to keep you from what you really should be doing, and if it weren’t for that dreadful magic staff, you’d never know how much time you were wasting.”

As he spoke, he tiptoed slowly toward them with his arms outstretched and continued to whisper in a soft, deceitful voice, “Now do come and stay with me. We’ll have so much fun together. There are things to fill and things to empty, things to take away and things to bring back, things to pick up and things to put down, and besides all that we have pencils to sharpen, holes to dig, nails to straighten, stamps to lick, and ever so much more. Why, if you stay here, you’ll never have to think again – and with a little practice you can become a monster of habit, too.”

They were all transfixed by the Trivium’s soothing voice, but just as he was about to clutch them in his well-manicured fingers a voice cried out, “RUN! RUN!”

Milo, who thought it was Tock, turned suddenly and dashed up the trail.

“RUN! RUN!” it shouted again, and this time Tock thought it was Milo and quickly followed him.

“RUN! RUN!” it urged once more, and now the Humbug, not caring who said it, ran desperately after his two friends, with the Terrible Trivium close behind.

“This way! This way!” the voice called again. They turned in its direction and scrambled up the difficult slippery rocks, sliding back at each step almost as far as they’d gone forward. With a great effort and many helping paws from Tock, they reached the top of the ridge at last, but only two steps ahead of the furious Trivium.

“Over here! Over here!” advised the voice, and without a moment’s hesitation they started through a puddle of sticky ooze, which quickly became ankle-deep, then knee-deep, then hip-deep, until finally they were struggling along through what felt very much like a waist-deep pool of peanut butter.

The Trivium, who had discovered a mound of pebbles which needed counting, followed no more, but stood at the edge shaking his fist, shouting horrible threats, and promising to rouse every demon in the mountains.

“What a nasty fellow,” gasped Milo, who was having great difficulty just getting his legs to move. “I hope I never meet him again.”

“I believe he’s stopped chasing us,” said the bug, looking back over his shoulder.

“It’s not what’s behind that worries me,” remarked Tock as they stepped from the sticky mess, “but what’s ahead.”

“Keep going straight! Keep going straight!” counseled the voice as they continued to pick their way carefully along the new path.

“Now step up! Now step up!” it recommended, and almost before they knew what had happened, they had all taken a step up and then plunged to the bottom of a deep murky pit.

“But he said up!” Milo complained bitterly from where he lay sprawling.

“Well, I hope you didn’t expect to get anywhere by listening to me,” said the voice gleefully.

“We’ll never get out of here,” the Humbug moaned, looking at the steep, smooth sides of the pit.

“That is quite an accurate evaluation of the situation,” said the voice coldly.

“Then why did you help us at all?” shouted Milo angrily.

“Oh, I’d do as much for anybody,” he replied; “bad advice is my specialty. For, as you can plainly see, I’m the long-nosed, green-eyed, curly-haired, wide-mouthed, thick-necked, broad-shouldered, round-bodied, short-armed, bowlegged, big-footed monster – and, if I do say so myself, one of the most frightening fiends in this whole wild wilderness. With me here, you wouldn’t dare try to escape.” And, with that, he shuffled to the edge of the pit and leered down at his helpless prisoners.

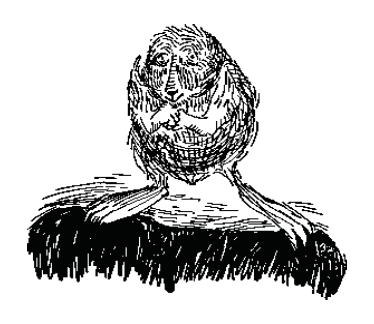

Tock and the Humbug turned away in fright, but Milo, who had learned by now that people are not always what they say they are, reached for his telescope and took a long look for himself. And there at the rim of the hole, instead of what he’d expected, stood a small furry creature with very worried eyes and a rather sheepish grin.

“Why, you’re not long-nosed, green-eyed, curly-haired, wide-mouthed, thick-necked, broad-shouldered, round-bodied, short-armed, bowlegged, or big-footed – and you’re not at all frightening,” said Milo indignantly. “What kind of a demon are you?”

The little creature, who seemed stunned at being found out, leaped back out of sight and began to whimper softly.

“I’m the demon of insincerity,” he sobbed. “I don’t mean what I say, I don’t mean what I do, and I don’t mean what I am. Most people who believe what I tell them go the wrong way, and stay there, but you and your awful telescope have spoiled everything. I’m going home.” And, crying hysterically, he stamped off in a huff.

“It certainly pays to have a good look at things,” observed Milo as he wrapped up the telescope with great care.

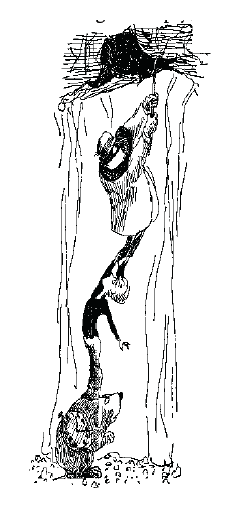

“Now all we have to do is climb out,” said Tock, placing his front paws as high on the wall as he could. “Here, hop up on my back.”

Milo climbed onto the dog’s shoulders. Then the bug crawled up both of them and, by standing on Milo’s head, just managed to hook his cane on the root of an old gnarled tree. With loud complaints he hung on doggedly until the other two had climbed out over him and pulled him up, somewhat dazed and discouraged.

“I’ll lead the way for a while,” he said, brushing himself off. “Follow me and we’ll stay out of trouble.”

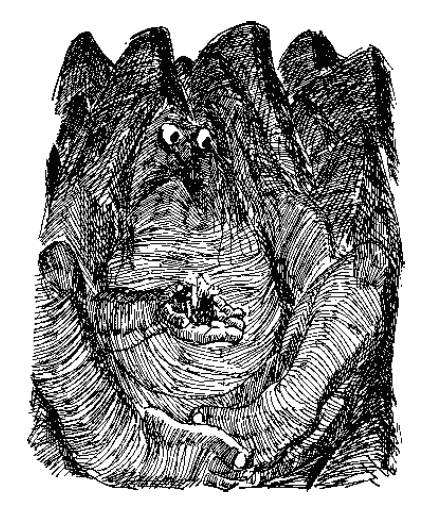

He guided them along one of five narrow ledges, all of which led to a grooved and rutted plateau. They stopped for a moment to rest and make plans, but before they had done either the whole mountain trembled violently and, with a sudden lurch, rose high into the air, carrying them along with it. For, quite accidentally, they had stepped into the callused hand of the Gelatinous Giant.

“AND WHAT HAVE WE HERE!” he roared, looking curiously at the tiny figures huddled in his palm – and licking his lips.

He was an incredible size even sitting down, with long unkempt hair, bulging eyes, and a shape hardly worth speaking of. He looked, in fact, very much like a colossal bowl of jelly, without the bowl.

“HOW DARE YOU DISTURB MY NAP!” he bellowed furiously, and the force of his hot breath tumbled them over in his hand.

“We’re terribly sorry,” said Milo meekly, when he’d untangled himself, “but you looked just like part of the mountain.”

“Naturally,” the giant replied in a more normal voice (but even this was like an explosion). “I have no shape of my own, so I try to be just like whatever I’m near. In the mountains I’m a lofty peak, on the beach a broad sand bar, in the forest a towering oak, and sometimes in the city I’m a very handsome twelve-story apartment house. I just hate to be conspicuous; it’s really not safe, you know.” Then he looked at them again with hungry eyes and wondered how well they’d taste.

“You look much too big to be afraid of anything,” said Milo quickly, for the giant had already begun to open his mouth wide.

“I’m not,” he said, with a slight shiver that ran all over his gelatinous body. “I’m afraid of everything. That’s why I’m so ferocious. If the others found out, I’d just die. Now do be quiet while I eat my breakfast.” He raised his hand toward his gaping mouth and the Humbug shut his eyes tightly and clasped both hands over his head.

“Then aren’t you really a fearful demon?” Milo asked desperately, on the assumption that the giant had been brought up well enough not to talk with a mouthful.

“Well, approximately yes,” he replied, lowering his arm to the vast relief of the bug; “that is, comparatively no. What I mean is, relatively maybe – in other words, roughly perhaps. What does everyone else think? There, you see,” he said peevishly; “I’m even afraid to make a positive statement. So please stop asking questions before I lose my appetite altogether.” Then he raised his arm again and prepared to swallow the three of them in one gulp.

“Why don’t you help us rescue Rhyme and Reason? Then maybe things will get better,” shouted Milo again, this time almost too late, for in another instant they would have all been gone.

“Oh, I wouldn’t do that,” said the Giant thoughtfully, lowering his arm once more. “I mean, why not leave well enough alone? That is, it’ll never work. I wouldn’t take a chance. In other words, let’s keep things as they are – changes are so frightening.” As he spoke he began to look a bit ill. “Maybe I’ll just eat one of you,” he remarked unhappily, “and save the rest for later. I don’t feel very well.”

“I have a better idea,” said Milo.

“You do?” interrupted the giant, losing any desire to eat at all. “If it’s one thing I can’t swallow, it’s ideas: they’re so hard to digest.”

“I have a box full of all the ideas in the world,” said Milo, proudly holding up the gift King Azaz had given him.

The thought of it terrified the giant, who began to shake like an enormous pudding.

“PUT ME DOWN AND JUST GO AWAY,” he pleaded, forgetting for a moment who had hold of whom; “AND PLEASE DON’T OPEN THAT BOX!”

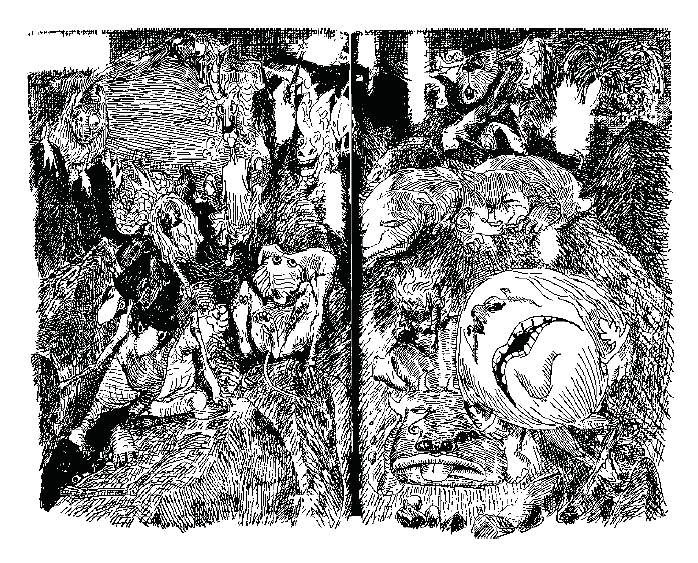

In another moment he’d set them down on the next jagged peak and, with panic in his eyes, lumbered off to warn the others of this terrible new threat. But news travels quickly. The Wordsnatcher, the Trivium, and the long-nosed, green-eyed, curly-haired, wide-mouthed, thick-necked, broad-shouldered, roundbodied, short-armed, bowlegged, big-footed monster had already spread the alarm throughout the evil, unenlightened mountains.

And out the demons came – from every cave and crevice, through every fissure and crack, from under the rocks and up from the mud, stomping and shuffling, slithering and sliding, through the murky shadows. And all had only one thought in mind: destroy the intruders and protect Ignorance.

From where they stood, Milo, Tock, and the Humbug could see them moving steadily forward, still far away but coming quickly. On all sides the cliffs were alive with this evil collection of crawling, looming, creeping, lurching shapes. Some could be seen plainly, others were but dim silhouettes, and yet still more, only now beginning to stir from their foul places, would be along much sooner than they were wanted.

“We’d better hurry,” barked Tock, “or they’re sure to catch us.” And he started up the trail again. Milo took one deep breath and did the same; and the bug, now that he knew what lay behind, ran ahead with renewed enthusiasm.

Higher and higher they climbed, in search of the castle and the two banished princesses – from one crest to the next, from jagged rock to jagged rock, up frightful crumbling cliffs and along desperately narrow ledges where a single misstep meant only good-by. An ominous silence dropped like a curtain around them and, except for the scuffling of their frantic footsteps, there wasn’t a sound. The world that Milo knew was a million thoughts away, and the demons – the demons were there in the distance.

“They’re gaining!” shouted the Humbug, wishing he’d never looked back.

“But there it is!” cried Milo at the same instant, for straight ahead, climbing up from atop the highest peak, was a spidery spiral stair, and at the other end stood the Castle in the Air.

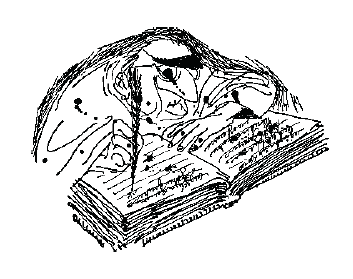

“I see it, I see it,” said the happy bug as they struggled up the twisting mountain trail. But what he didn’t see was that, curled up right in front of the first step, was a little round man in a frock coat, sleeping peacefully on a very large and wellworn ledger. A long quill pen sat precariously behind his ear, there were inkstains all over his hands and face as well as his clothing, and he wore a pair of the thickest eyeglasses that Milo had ever seen.

“Be very careful,” whispered Tock when they’d finally reached the top, and the Humbug stepped gingerly around and started up the stairs.

“NAMES?” the little man called out briskly, just as the startled bug reached the first step. He sat up quickly, pulled the book out from under him, put on a green eyeshade, and waited with his pen poised in the air.

“Well, I… “ stammered the bug.

“NAMES?” he cried again, and as he did he opened the book to page 512 and began to write furiously. The quill made horrible scratching noises, and the point, which was continually catching in the paper, flicked tiny inkblots all over him. As they called out their names, he noted them carefully in alphabetical order.

“Splendid, splendid, splendid,” he muttered to himself. “I haven’t had an M in ages.”

“What do you want our names for?” asked Milo, looking anxiously over his shoulder. “We’re in a bit of a hurry.”

“Oh, this won’t take a minute,” the man assured them. “I’m the official Senses Taker, and I must have some information before I can take your senses. Now, if you’ll just tell me when you were born, where you were born, why you were born, how old you are now, how old you were then, how old you’ll be in a little while, your mother’s name, your father’s name, your aunt’s name, your uncle’s name, your cousin’s name, where you live, how long you’ve lived there, the schools you’ve attended, the schools you haven’t attended, your hobbies, your telephone number, your shoe size, shirt size, collar size, hat size, and the names and addresses of six people who can verify all this information, we’ll get started. One at a time, please; stand in line; and no pushing, no talking, no peeking.”

The Humbug, who had difficulty remembering anything, went first. The little man leisurely recorded each answer in five different places, pausing often to polish his glasses, clear his throat, straighten his tie, and blow his nose. He managed also to cover the distressed bug from head to foot in ink.

“NEXT!” he announced very officially.

“I do wish he’d hurry,” said Milo, stepping forward, for in the distance he could see the first of the demons already beginning to scale the mountain toward them, no more than a few minutes away.

The little man wrote with painful deliberation, finally finished with both Milo and Tock, and looked up happily.

“May we go now?” asked the dog, whose sensitive nose had picked up a loathsome, evil smell that grew stronger every second.

“By all means,” said the man agreeably, “just as soon as you finish telling me your height; your weight; the number of books you read each year; the number of books you don’t read each year; the amount of time you spend eating, playing, working, and sleeping every day; where you go on vacations; how many ice-cream cones you eat in a week; how far it is from your house to the barbershop; and which is your favorite color. Then, after that, please fill out these forms and applications – three copies of each – and be careful, for if you make one mistake, you’ll have to do them all over again.”

“Oh dear,” said Milo, looking at the pile of papers, “we’ll never finish these.” And even as he spoke the demons swarmed stealthily up the mountain.

“Come, come,” said the Senses Taker, chuckling gaily to himself, “don’t take all day. I’m expecting several more visitors any minute now.”

They set to work feverishly on the difficult forms, and when they’d finished, Milo placed them all in the little man’s lap. He thanked them politely, took off his eyeshade, put the pen behind his ear, closed the book, and went back to sleep. The Humbug took one horrified look back over his shoulder and quickly started up the stairs.

“DESTINATION?” shouted the Senses Taker, sitting up again, putting on his eyeshade, taking the pen from behind his ear, and opening his book.

“But I thought…” protested the astonished bug

“DESTINATION?” he repeated, making several notations in the ledger.

“The Castle in the Air,” said Milo impatiently.

“Why bother?” said the Senses Taker, pointing into the distance. “I’m sure you’d rather see what I have to show you.”

As he spoke, they all looked up, but only Milo could see the gay and exciting circus there on the horizon. There were tents and side shows and rides and even wild animals – everything a little boy could spend hours watching.

“And wouldn’t you enjoy a more pleasant aroma?” he said, turning to Tock.

Almost immediately the dog smelled a wonderful smell that no one but he could smell. It was made up of all the marvelous things that had ever delighted his curious nose.

“And here’s something I know you’ll enjoy hearing,” he assured the Humbug.

The bug listened with rapt attention to something he alone could hear – the shouts and applause of an enormous crowd, all cheering for him.

They each stood as if in a trance, looking, smelling, and listening to the very special things that the Senses Taker had provided for them, forgetting completely about where they were going and who, with evil intent, was coming up behind them.

The Senses Taker sat back with a satisfied smile on his puffy little face as the demons came closer and closer, until less than a minute separated them from their helpless victims.But Milo was too engrossed in the circus to notice, and Tock had closed his eyes, the better to smell, and the bug, bowing and waving, stood with a look of sheer bliss on his face, interested only in the wild ovation.

The little man had done his work well and, except for some ominous crawling noises just below the crest of the mountain, everything was again silent. Milo, who stood staring blankly into the distance, let his bag of gifts slip from his shoulder to the ground. And, as he did, the package of sounds broke open, filling the air with peals of happy laughter which seemed so gay that first he, then Tock, and finally the Humbug joined in. And suddenly the spell was broken.

“There is no circus,” cried Milo, realizing he’d been tricked.

“There were no smells,” barked Tock, his alarm now ringing furiously.

“The applause is gone,” complained the disappointed Humbug.

I warned you; I warned you I was the Senses Taker,” sneered the Senses Taker. “I help people find what they’re not looking for, hear what they’re not listening for, run after what they’re not chasing, and smell what isn’t even there. And, furthermore,” he cackled, hopping around gleefully on his stubby legs, “I’ll steal your sense of purpose, take your sense of duty, destroy your sense of proportion – and, but for one thing, you’d be helpless yet.”

“What’s that?” asked Milo fearfully.

“As long as you have the sound of laughter,” he groaned unhappily, “I cannot take your sense of humor – and, with it, you’ve nothing to fear from me.”

“But what about THEM?” cried the terrified bug, for at that very instant the other demons had reached the top at last and were leaping forward to seize them.

They ran for the stairs, bowling over the disconsolate Senses Taker, ledger, ink bottle, eyeshade, and all, as they went. The Humbug dashed up first, then Tock, and lastly Milo, almost too late, as a scaly arm brushed his shoe.

The dangerous stairs danced dizzily in the wind, and the clumsy demons refused to follow; but they howled with rage and fury, swore bloody vengeance, and watched with many pairs of burning eyes as the three small shapes vanished slowly into the clouds.

“Don’t look down,” advised Milo as the bug tottered upward on unsteady legs.

Like a giant corkscrew, the stairway twisted through the darkness, steep and narrow and with no rail to guide them. The wind howled cruelly in an effort to tear them loose, and the fog dragged clammy fingers down their backs; but up the giddy flight they went, each one helping the others, until at last the clouds parted, the darkness fell away, and a glow of golden sunrays warmed their arrival. The castle gate swung smoothly open, and on a rug as soft as a snowdrift they entered the great hall and they stood shyly waiting.

“Come right in, please; we’ve been expecting you,” sang out two sweet voices in unison.

At the far end of the hall a silver curtain parted and two young women stepped forward. They were dressed all in white and were beautiful beyond compare. One was grave and quiet, with a look of warm understanding in her eyes, and the other seemed gay and joyful.

“You must be the Princess of Pure Reason,” said Milo, bowing to the first.

She answered simply, “Yes,” and that was just enough.

“Then you are Sweet Rhyme,” he said, with a smile to the other.

Her eyes sparkled brightly and she answered with a laugh as friendly as the mailman’s ring when you know there’s a letter for you.

“We’ve come to rescue you both,” Milo explained very seriously.

“And the demons are close behind,” said the worried Humbug, still shaky from his ordeal.

“And we should leave right away,” advised Tock.

“Oh, they won’t dare come up here,” said Reason gently; “and we’ll be down there soon enough.”

“Why not sit for a moment and rest?” suggested Rhyme. “I’m sure you must be tired. Have you been traveling long?”

“Days,” sighed the exhausted dog, curling up on a large downy cushion.

“Weeks,” corrected the bug, flopping into a deep comfortable armchair, for it did seem that way to him.

“It has been a long trip,” said Milo, climbing onto the couch where the princesses sat; “but we would have been here much sooner if I hadn’t made so many mistakes. I’m afraid it’s all my fault.”

“You must never feel badly about making mistakes,” explained Reason quietly, “as long as you take the trouble to learn from them. For you often learn more by being wrong for the right reasons than you do by being right for the wrong reasons.”

“But there’s so much to learn,” he said, with a thoughtful frown.

“Yes, that’s true,” admitted Rhyme; “but it’s not just learning things that’s important. It’s learning what to do with what you learn and learning why you learn things at all that matters.”

“That’s just what I mean,” explained Milo, as Tock and the exhausted bug drifted quietly off to sleep.

“Many of the things I’m supposed to know seem so useless that I can’t see the purpose in learning them at all.”

“You may not see it now,” said the Princess of Pure Reason, looking knowingly at Milo’s puzzled face, “but whatever we learn has a purpose and whatever we do affects everything and everyone else, if even in the tiniest way. Why, when a housefly flaps his wings, a breeze goes round the world; when a speck of dust falls to the ground, the entire planet weighs a little more; and when you stamp your foot, the earth moves slightly off its course. Whenever you laugh, gladness spreads like the ripples in a pond; and whenever you’re sad, no one anywhere can be really happy. And it’s much the same thing with knowledge, for whenever you learn something new, the whole world becomes that much richer.”

“And remember, also,” added the Princess of Sweet Rhyme, “that many places you would like to see are just off the map and many things you want to know are just out of sight or a little beyond your reach. But someday you’ll reach them all, for what you learn today, for no reason at all, will help you discover all the wonderful secrets of tomorrow.”

“I think I understand,” he said, still full of questions and thoughts; “but which is the most important…”

At that moment the conversation was interrupted by a far-off chopping noise. With each loud blow, the entire room and everything in it shook and rattled. Down below, on the murky peak, the demons were busily cutting the stairway loose with axes and hammers and saws. Before long the whole thing collapsed with a tremendous crash and the startled Humbug leaped to his feet just in time to see the castle drifting slowly off into space.

“We’re moving!” he shouted, which was a fact that had already become obvious to everyone.

“I think we had better leave now,” said Rhyme softly, and Reason agreed with a nod.

“But how will we get down?” groaned the Humbug, looking at the wreckage below. “There’s no stairway and we’re sailing higher every minute.”

“Well, time flies, doesn’t it?” asked Milo.

“On many occasions,” barked Tock, jumping eagerly to his feet. “I’ll take everyone down.”

“Can you carry us all?” inquired the bug.

“For a short distance,” said the dog thoughtfully.

“The princesses can ride on my back, Milo can catch hold of my tail, and you can hang on to his ankles.”

“But what of the Castle in the Air?” the bug objected, not very pleased with the arrangement.

“Let it drift away,” said Rhyme.

“And good riddance,” added Reason, “for no matter how beautiful it seems, it’s still nothing but a prison.”

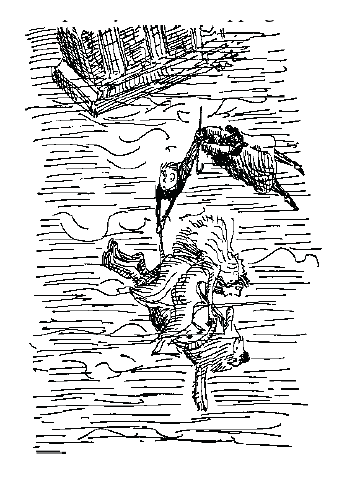

Tock then backed up three steps and, with a running start, bounded through the window with all his passengers and began the long glide down. The princesses sat tall and unafraid, Milo held on as tight as he could, and the bug swung crazily, like the tail on a kite. Down through the darkness they plunged, to the mountains and the monsters below.

Sailing past three of the tallest peaks, and just over the outstretched arms of the grasping demons, they reached the ground and landed with a sudden jolt.

“Quick!” urged Tock. “Follow me! We’ll have to run for it.”

With the princesses still on his back, he galloped down the rocky trail – and not a moment too soon. For, pounding down the mountainside, in a cloud of clinging dust and a chorus of chilling shrieks, came all the loathsome creatures who choose to live in Ignorance and who had waited so very impatiently.

Thick black clouds hung heavily overhead as they fled through the darkness, and Milo, looking back for just a moment, could see the awful shapes coming closer and closer. Just to the left, and not very far away, were the Triple Demons of Compromise – one tall and thin, one short and fat, and the third exactly like the other two. As always, they moved in ominous circles, for if one said “here,” the other said “there,” and the third agreed perfectly with both of them. And, since they always settled their differences by doing what none of them really wanted, they rarely got anywhere at all – and neither did anyone they met.

Jumping clumsily from boulder to boulder and catching hold with his cruel, curving claws was the Horrible Hopping Hindsight, a most unpleasant fellow whose eyes were in the rear and whose rear was out in front. He invariably leaped before he looked and never cared where he was going as long as he knew why he shouldn’t have gone to where he’d been.

And, most terrifying of all, directly behind, inching along like giant soft-shelled snails, with blazing eyes and wet anxious mouths, came the Gorgons of Hate and Malice, leaving a trail of slime behind them and moving much more quickly than you’d think.

“FASTER!” shouted Tock. “They’re closing in.”

Down from the heights they raced, the Humbug with one hand on his hat and the other flailing desperately in the air, Milo running as he never ran before, and the demons just a little bit faster than that. From off on the right, his heavy bulbous body lurching dangerously on the spindly legs which barely supported him, came the Overbearing Know-it-all, talking continuously. A dismal demon who was mostly mouth, he was ready at a moment’s notice to offer misinformation on any subject. And, while he often tumbled heavily, it was never he who was hurt, but, rather, the unfortunate person on whom he fell.

Next to him, but just a little behind, came the Gross Exaggeration, whose grotesque features and thoroughly unpleasant manners were hideous to see, and whose rows of wicked teeth were made only to mangle the truth. They hunted together, and were bad luck to anyone they caught.

Riding along on the back of anyone who’d carry him was the Threadbare Excuse, a small, pathetic figure whose clothes were worn and tattered and who mumbled the same things again and again, in a low but piercing voice: “Well, I’ve been sick – but the page was torn out – I missed the bus – but no one else did it – well, I’ve been sick – but the page was torn out – I missed the bus – but no one else did it.” He looked quite harmless and friendly but, once he grabbed on, he almost never let go.

Closer and closer they came, bumping and jolting each other, clawing and snorting in their eager fury. Tock staggered along bravely with Rhyme and Reason, Milo’s lungs now felt ready to burst as he stumbled down the trail, and the Humbug was slowly falling behind. Gradually the path grew broader and more flat as it reached the bottom of the mountain and turned toward Wisdom. Ahead lay light and safety – but perhaps just a bit too far away.

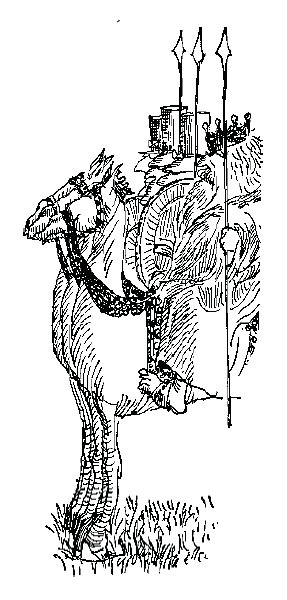

And down came the demons from everywhere, frenzied creatures of darkness, lurching wildly toward their prey. From off in the rear, the Terrible Trivium and the wobbly Gelatinous Giant urged them on with glee. And pounding forward with a rush came the ugly Dilemma, snorting steam and looking intently for someone to catch on the ends of his long pointed horns, while his hoofs bit eagerly at the ground.

The exhausted Humbug swayed and tottered on his rubbery legs, a look of longing on his anguished face.

“I don’t think I can “ he gasped, as a jagged slash of lightning ripped open the sky and the thunder stole his words.

Closer and closer the demons loomed as the desperate chase neared its end. Then, gathering themselves for one final leap, they prepared to engulf first the bug, then the boy, and lastly the dog and his two passengers. They rose as one and…

And suddenly stopped, as if frozen in mid-air, unable to move, staring ahead in terror.

Milo slowly raised his weary head, and there in the horizon, for as far as the eye could see, stood the massed armies of Wisdom, the sun glistening from their swords and shields, and their bright banners slapping proudly at the breeze.

For a moment everything was silent. Then a thousand trumpets sounded – then a thousand more – and, like an ocean wave, the long line of horsemen advanced, slowly at first, then faster and faster, until with a gallop and a shout, which was music to Milo’s ears, they swept forward toward the horrified demons. There in the lead was King Azaz, his dazzling armor embossed with every letter in the alphabet, and, with him, the Mathemagician, brandishing a freshly sharpened staff. From his tiny wagon, Dr. Dischord hurled explosion after explosion, to the delight of the Soundkeeper, while the busy DYNNE collected them almost at once. And, in honor of the occasion, Chroma the Great led his orchestra in a stirring display of patriotic colors. Everyone Milo had met during his journey had come to help – the men of the market place, the miners of Digitopolis, and all the good people from the valley and the forest.

The Spelling Bee buzzed excitedly overhead shouting,

“Charge – c-h-a-r-g-e – charge – c-h-a-r-g-e.”

Canby, who, as everyone knew, was as cowardly as can be, came all the way from Conclusions to show that he was also as brave. And even Officer Shrift, mounted proudly on a long, low dachshund, galloped grimly along. Cringing with fear, the monsters of Ignorance turned in flight and, with anguished cries too horrible ever to forget, returned to the damp, dark places from which they came. The Humbug sighed with relief, and Milo and the princesses prepared to greet the victorious army.

“Well done,” stated the Duke of Definition, dismounting and grasping Milo’s hand warmly.

“Fine job,” seconded the Minister of Meaning.

“Good Work,” added the Count of Connotation.

“Congratulations,” proposed the Earl of Essence.

“CHEERS,” recommended the Undersecretary of Understanding.

And, since that’s exactly what everyone felt like doing, that’s exactly what everyone did.

“It’s we who should thank “ began Milo, when the shouting had subsided, but, before he could finish, they had unrolled an enormous scroll. And, with a fanfare of trumpets and drums, they stated in order that:

“Henceforth,”

“And forthwith,”

“Let it be known by all men”

“That Rhyme and Reason”

“Reign once more in Wisdom.”

The two princesses bowed gratefully and warmly kissed their brothers, and they all agreed that a very fine thing had happened.

“And furthermore,” continued the proclamation,

“The boy named Milo”

“The dog known as Tock,”

“And the insect hereinafter referred to as the Humbug”

“Are hereby declared to be”

“Heroes of the realm.”

Cheer after cheer filled the air, and even the bug seemed a bit embarrassed at having so much attention paid to him.

“Therefore,” concluded the duke, “In honor of their glorious deed, a royal holiday is declared. Let there be parades through every city in the land and a gala carnival of three days’ duration, consisting of jousts, games, feasts, and follies.”

The five cabinet members then rolled up the large parchment and, with many bows and flourishes, retired. Swift horsemen carried the news to every corner of the kingdom, and, as the parade slowly wound its way through the countryside, crowds of people gathered to cheer it along. Garlands of flowers hung from every house and shop and carpeted the streets. Even the air shimmered with excitement, and shutters closed for many years were thrown open to let the brilliant sunlight shine where it hadn’t shone in so long. Milo, Tock, and the very subdued Humbug sat proudly in the royal carriage with Azaz, the Mathemagician, and the two princesses; and the parade stretched for miles in both directions.

As the cheering continued, Rhyme leaned forward and touched Milo gently on the arm.

“They’re shouting for you,” she said with a smile.

“But I could never have done it,” he objected, “without everyone else’s help.”

“That may be true,” said Reason gravely, “but you had the courage to try; and what you can do is often simply a matter of what you will do.”

“That’s why,” said Azaz, “there was one very important thing about your quest that we couldn’t discuss until you returned.”

“I remember,” said Milo eagerly. “Tell me now.”

“It was impossible,” said the king, looking at the Mathemagician.

“Completely impossible,” said the Mathemagician, looking at the king. “Do you mean…“ stammered the bug, who suddenly felt a bit faint.

“Yes, indeed,” they repeated together; “but if we’d told you then, you might not have gone – and, as you’ve discovered, so many things are possible just as long as you don’t know they’re impossible.”

And for the remainder of the ride Milo didn’t utter a sound.

Finally, when they’d reached a broad, flat plain midway between Dictionopolis and Digitopolis, somewhat to the right of the Valley of Sound and a little to the left of the Forest of Sight, the long line of carriages and horsemen stopped, and the great carnival began.

Gaily striped tents and pavilions sprang up everywhere as the workmen scurried about like ants. Within minutes there were racecourses and grandstands, side shows and refreshment booths, gaming fields, Ferris wheels, banners, bunting, and bedlam, almost without pause.

The Mathemagician provided a continuous display of brilliant fireworks made up of exploding numbers which multiplied and divided with breath-taking results – the colors, of course, being supplied by Chroma and the noise by a deliriously happy Dr. Dischord. Thanks to the Soundkeeper, there was music and laughter and, for very brief moments, even a little silence.

Alec Bings set up an enormous telescope and invited everyone to see the other side of the moon, and the Humbug wandered through the crowd accepting congratulations and recounting in great detail his brave exploits, most of which gained immeasurably in the telling. And each evening, just at sunset, a royal banquet was held. There was everything imaginable to eat. King Azaz had ordered a special supply of delicious words in all flavors and, for those who liked exotic foods, in all languages, too. The Mathemagician had provided innumerable platters of division dumplings, which Milo was very careful to avoid, for, no matter how many you ate, when you finished there was more on your plate than when you began.

And, of course, following the meal came songs, epic poems, and speeches in praise of the princesses and the three gallant adventurers who had rescued them. King Azaz and the Mathemagician pledged that every year at this same time they would lead their armies to the mountains of Ignorance until not one demon remained, and everyone agreed that no finer carnival for no finer reason had ever been held in Wisdom.

But even things as fine as all that must end sometime, and late on the afternoon of the third day the tents were struck, the pavilions were folded, and everything was packed ready to leave.

“It’s time to go now,” said Reason, “for there is much to do.” And, as she spoke, Milo suddenly remembered his home. He wanted very much to go back, yet somehow he could not bear the thought of leaving.

“And so you must say good-by,” said Rhyme, patting him gently on the cheek.

“To everyone?” said Milo unhappily. He looked around slowly at all the friends he’d made, and he looked very hard so as not to forget any of them for even an instant. But mostly he looked at Tock and the Humbug, with whom he had shared so much – the perils, the dangers, the fears, and, best of all, the victory. Never had anyone had two more steadfast companions.

“Can’t you both come with me?” he asked, knowing the answer as he said it.

“I’m afraid not, old man,” replied the bug. “I’d like, to, but I’ve arranged a lecture tour which will keep me occupied for years.”

“And they do need a watchdog here,” barked Tock sadly.

Milo embraced the bug who, in his most typical fashion, was heard to mumble gruffly, “BAH,” but whose damp eyes told quite a different story. Then the boy threw his arms around Tock’s neck and, for just a moment, held on very tightly.

“Thank you for everything you’ve taught me,” said Milo to everybody as a tear rolled down his cheek.

“And thank you for what you’ve taught us,” said the king – and, as he clapped his hands, the little car was brought forward, polished like new.

Milo got in and, with one last look, started down the road, with everyone waving him on.

“Good-by,” he shouted. “Good-by. I’ll be back.”

“Good-by,” shouted Azaz. “Always remember the importance of words.”

“And numbers,” added the Mathemagician forcefully.

“Surely you don’t think numbers are as important as words?” he heard Azaz shout from the distance.

“Is that so?” replied the Mathemagician a little more faintly. “Why, if “

“Oh dear,” thought Milo; “I do hope they don’t start it all again.” And in a moment they had faded from sight as the road dipped, turned, and headed for home.

As the pleasant countryside flashed by and the wind whistled a tune on the windshield, it suddenly occurred to Milo that he must have been gone for several weeks.

“I do hope that no one’s been worried,” he thought, urging the car on faster. “I’ve never been away this long before.”

The late-afternoon sun had turned now from a vivid yellow to a warm lazy orange, and it seemed almost as tired as he was. The road raced ahead in a series of gentle curves that began to look familiar, and off in the distance the solitary tollbooth appeared, a welcome sight indeed. In a few minutes he reached the end of his journey, deposited his coin, and drove through. And, almost before realizing it, he was sitting in the middle of his own room again.

“It’s only six o’clock,” he observed with a yawn, and then, in a moment, he made an even more interesting discovery. “And it’s still today! I’ve been gone for only an hour!” he cried in amazement, for he’d certainly never realized how much he could do in so short a time.

Milo was much too tired to talk and almost too tired for dinner, so, without a murmur, he went off to bed as soon as he could. He pulled the covers around him, took a last look at his room – which somehow seemed very different than he’d remembered – and then drifted into a deep and welcome sleep. School went very quickly the next day, but not quickly enough, for Milo’s head was full of plans and his eyes could see nothing but the tollbooth and what lay beyond.

He waited impatiently for the end of class, and when the time finally came, his feet raced his thoughts all the way back to the house. “Another trip! Another trip! I’ll leave right away. They’ll all be so glad to see me, and I’ll…”

He stopped abruptly at the door of his room, for, where the tollbooth had been just the night before, there was now nothing at all. He searched frantically throughout the apartment, but it had vanished just as mysteriously as it had come – and in its place was another bright-blue envelope, which was addressed simply:

“FOR MILO, WHO NOW KNOWS THE WAY.”

He opened it quickly and read:

Dear Milo,

You have now completed your trip, courtesy of the Phantom Tollbooth. We trust that everything has been satisfactory, and hope you understand why we had to come and collect it. You see, there are so many other boys and girls waiting to use it, too.

It’s true that there are many lands you’ve still to visit (some of which are not even on the map) and wonderful things to see (that no one has yet imagined), but we’re quite sure that if you really want to, you’ll find a way to reach them all by yourself.

Yours truly,

The signature was blurred and couldn’t be read.

Milo walked sadly to the window and squeezed himself into one corner of the large armchair. He felt very lonely and desolate as his thoughts turned far away – to the foolish, lovable bug; to the comforting assurance of Tock, standing next to him; to the erratic, excitable DYNNE; to little Alec, who, he hoped, would someday reach the ground; to Rhyme and Reason, without whom Wisdom withered; and to the many, many others he would remember always. And yet, even as he thought of all these things, he noticed somehow that the sky was a lovely shade of blue and that one cloud had the shape of a sailing ship. The tips of the trees held pale, young buds and the leaves were a rich deep green. Outside the window, there was so much to see, and hear, and touch – walks to take, hills to climb, caterpillars to watch as they strolled through the garden. There were voices to hear and conversations to listen to in wonder, and the special smell of each day.

And, in the very room in which he sat, there were books that could take you anywhere, and things to invent, and make, and build, and break, and all the puzzle and excitement of everything he didn’t know – music to play, songs to sing, and worlds to imagine and then someday make real. His thoughts darted eagerly about as everything looked new – and worth trying.

“Well, I would like to make another trip,” he said, jumping to his feet; “but I really don’t know when I’ll have the time. There’s just so much to do right here.”