For reference, click here for a map of The Lands Beyond

Up ahead, the road divided into three and, as if in reply to Milo’s question, an enormous road sign, pointing in all three directions, stated clearly:

DIGITOPOLIS

5 Miles

1,600 Rods

8,800 Yards

26,400 Feet

316,800 Inches

633,600 Half inches

AND THEN SOME

“Let’s travel by miles,” advised the Humbug; “it’s shorter.”

“Let’s travel by half inches,” suggested Milo; “it’s quicker.”

“But which road should we take?” asked Tock. “It must make a difference.”

As they argued, a most peculiar little figure stepped nimbly from behind the sign and approached them, talking all the while. “Yes, indeed; indeed it does; certainly; my, yes; it does make a difference; undoubtedly.”

He was constructed (for that’s really the only way to describe him) of a large assortment of lines and angles connected together into one solid many-sided shape – somewhat like a cube that’s had all its corners cut off and then had all its corners cut off again. Each of the edges was neatly labeled with a small letter, and each of the angles with a large one. He wore a handsome beret on top, and peering intently from one of his several surfaces was a very serious face. Perhaps if you look at the picture you’ll know what I mean.

When he reached the car, the figure doffed his cap and recited in a loud clear voice:

“My angles are many.

My sides are not few.

I’m the Dodecahedron.

Who are you?”

“What’s a Dodecahedron?” inquired Milo, who was barely able to pronounce the strange word.

“See for yourself,” he said, turning around slowly. “A Dodecahedron is a mathematical shape with twelve faces.”

Just as he said it, eleven other faces appeared, one on each surface, and each one wore a different expression. “I usually use one at a time,” he confided, as all but the smiling one disappeared again. “It saves wear and tear. What are you called?”

“Milo,” said Milo.

“That is an odd name,” he said, changing his smiling face for a frowning one. “And you only have one face.”

“Is that bad?” asked Milo, making sure it was still there.

“You’ll soon wear it out using it for everything,” replied the Dodecahedron. “Now I have one for smiling, one for laughing, one for crying, one for frowning, one for thinking, one for pouting, and six more besides. Is everyone with one face called a Milo?”

“Oh no,” Milo replied; “some are called Henry or George or Robert or John or lots of other things.”

“How terribly confusing,” he cried. “Everything here is called exactly what it is. The triangles are called triangles, the circles are called circles, and even the same numbers have the same name. Why, can you imagine what would happen if we named all the twos Henry or George or Robert or John or lots of other things? You’d have to say Robert plus John equals four, and if the four’s name were Albert, things would be hopeless.”

“I never thought of it that way,” Milo admitted.

“Then I suggest you begin at once,” admonished the Dodecahedron from his admonishing face, “for here in Digitopolis everything is quite precise.”

“Then perhaps you can help us decide which road to take,” said Milo.

“By all means,” he replied happily. “There’s nothing to it. If a small car carrying three people at thirty miles an hour for ten minutes along a road five miles long at 11:35 in the morning starts at the same time as three people who have been traveling in a little automobile at twenty miles an hour for fifteen minutes on another road exactly twice as long as one half the distance of the other, while a dog, a bug, and a boy travel an equal distance in the same time or the same distance in an equal time along a third road in mid-October, then which one arrives first and which is the best way to go?”

“Seventeen!” shouted the Humbug, scribbling furiously on a piece of paper.

“Well, I’m not sure, but “ Milo stammered after several minutes of frantic figuring.

“You’ll have to do better than that,” scolded the Dodecahedron, “or you’ll never know how far you’ve gone or whether or not you’ve ever gotten there.”

“I’m not very good at problems,” admitted Milo.

“What a shame,” sighed the Dodecahedron. “They’re so very useful. Why, did you know that if a beaver two feet long with a tail a foot and a half long can build a dam twelve feet high and six feet wide in two days, all you would need to build Boulder Dam is a beaver sixty-eight feet long with a fifty-one-foot tail?”

“Where would you find a beaver that big?” grumbled the Humbug as his pencil point snapped.

“I’m sure I don’t know,” he replied, “but if you did, you’d certainly know what to do with him.”

“That’s absurd,” objected Milo, whose head was spinning from all the numbers and questions.

“That may be true,” he acknowledged, “but it’s completely accurate, and as long as the answer is right, who cares if the question is wrong? If you want sense, you’ll have to make it yourself.”

“All three roads arrive at the same place at the same time,” interrupted Tock, who had patiently been doing the first problem.

“Correct!” shouted the Dodecahedron. “And I’ll take you there myself. Now you can see how important problems are. If you hadn’t done this one properly, you might have gone the wrong way.”

“I can’t see where I made my mistake,” said the Humbug, frantically rechecking his figures.

“But if all the roads arrive at the same place at the same time, then aren’t they all the right way?” asked Milo.

“Certainly not!” he shouted, glaring from his most upset face. “They’re all the wrong way. Just because you have a choice, it doesn’t mean that any of them has to be right.”

He walked to the sign and quickly spun it around three times. As he did, the three roads vanished and a new one suddenly appeared, heading in the direction that the sign now pointed.

“Is every road five miles from Digitopolis?” asked Milo.

“I’m afraid it has to be,” the Dodecahedron replied, leaping onto the back of the car. “It’s the only sign we’ve got.”

The new road was quite bumpy and full of stones, and each time they hit one, the Dodecahedron bounced into the air and landed on one of his faces, with a sulk or a smile or a laugh or a frown, depending upon which one it was.

“We’ll soon be there,” he announced happily, after one of his short flights. “Welcome to the land of numbers.”

“It doesn’t look very inviting,” the bug remarked, for, as they climbed higher and higher, not a tree or a blade of grass could be seen anywhere. Only the rocks remained.

“Is this the place where numbers are made?” asked Milo as the car lurched again, and this time the Dodecahedron sailed off down the mountainside, head over heels and grunt over grimace, until he landed sad side up at what looked like the entrance to a cave.

“They’re not made,” he replied, as if nothing had happened. “You have to dig for them. Don’t you know anything at all about numbers?”

“Well, I don’t think they’re very important,” snapped Milo, too embarrassed to admit the truth.

“NOT IMPORTANT!” roared the Dodecahedron, turning red with fury. “Could you have tea for two without the two – or three blind mice without the three? Would there be four corners of the earth if there weren’t a four? And how would you sail the seven seas without a seven?”

“All I meant was “ began Milo, but the Dodecahedron, overcome with emotion and shouting furiously, carried right on.

“If you had high hopes, how would you know how high they were? And did you know that narrow escapes come in all different widths? Would you travel the whole wide world without ever knowing how wide it was? And how could you do anything at long last,” he concluded, waving his arms over his head, “without knowing how long the last was? Why, numbers are the most beautiful and valuable things in the world. Just follow me and I’ll show you.” He turned on his heel and stalked off into the cave.

“Come along, come along,” he shouted from the dark hole. “I can’t wait for you all day.” And in a moment they’d followed him into the mountain. It took several minutes for their eyes to become accustomed to the dim light, and during that time strange scratching, scraping, tapping, scuffling noises could be heard all around them.

“Put these on,” instructed the Dodecahedron, handing each of them a helmet with a flashlight attached to the top.

“Where are we going?” whispered Milo, for it seemed like the kind of place in which you whispered.

“We’re here,” he replied with a sweeping gesture. “This is the numbers mine.”

Milo squinted into the darkness and saw for the first time that they had entered a vast cavern lit only by a soft, eerie glow from the great stalactites which hung ominously from the ceiling. Passages and corridors honeycombed the walls and wound their way from floor to ceiling, up and down the sides of the cave. And, everywhere he looked, Milo saw little men no bigger than himself busy digging and chopping, shoveling and scraping, pulling and tugging carts full of stone from one place to another.

“Right this way,” instructed the Dodecahedron, “and watch where you step.”

As he spoke, his voice echoed and re-echoed and reechoed again, mixing its sound with the buzz of activity all around them. Tock trotted along next to Milo, and the Humbug, stepping daintily, followed behind. “Whose mine is it?” asked Milo, stepping around two of the loaded wagons.

“BY THE FOUR MILLION EIGHT HUNDRED AND TWENTY-SEVEN THOUSAND SIX HUNDRED AND FIFTY-NINE HAIRS ON MY HEAD, IT’S MINE, OF COURSE!” bellowed a voice from across the cavern.

And striding toward them came a figure who could only have been the Mathemagician. He was dressed in a long flowing robe covered entirely with complex mathematical equations and a tall pointed cap that made him look very wise. In his left hand he carried a long staff with a pencil point at one end and a large rubber eraser at the other.

“It’s a lovely mine,” apologized the Humbug, who was always intimidated by loud noises.

“The biggest number mine in the kingdom,” said the Mathemagician proudly.

“Are there any precious stones in it?” asked Milo excitedly.

“PRECIOUS STONES!” he roared, even louder than before. And then he leaned over toward Milo and whispered softly, “By the eight million two hundred and forty-seven thousand three hundred and twelve threads in my robe, I’ll say there are. Look here.”

He reached into one of the carts and pulled out a small object, which he polished vigorously on his robe. When he held it up to the light, it sparkled brightly.

“But that’s a five,” objected Milo, for that was certainly what it was.

“Exactly,” agreed the Mathemagician; “as valuable a jewel as you’ll find anywhere. Look at some of the others.”

He scooped up a great handful of stones and poured them into Milo’s arms. They included all the numbers from one to nine, and even an assortment of zeros.

“We dig them and polish them right here,” volunteered the Dodecahedron, pointing to a group of workers busily employed at the buffing wheels; “and then we send them all over the world. Marvelous, aren’t they?”

“They are exceptional,” said Tock, who had a special fondness for numbers.

“So that’s where they come from,” said Milo, looking in awe at the glittering collection of numbers. He returned them to the Dodecahedron as carefully as possible but, as he did, one dropped to the floor with a smash and broke in two. The Humbug winced and Milo looked terribly concerned.

“Oh, don’t worry about that,” said the Mathemagician as he scooped up the pieces. “We use the broken ones for fractions.”

“Haven’t you any diamonds or emeralds or rubies?” asked the bug irritably, for he was quite disappointed in what he’d seen so far.

“Yes, indeed,” the Mathemagician replied, leading them to the rear of the cave; “right this way.”

There, piled into enormous mounds that reached almost to the ceiling, were not only diamonds and emeralds and rubies but also sapphires, amethysts, topazes, moonstones, and garnets. It was the most amazing mass of wealth that any of them had ever seen.

“They’re such a terrible nuisance,” sighed the Mathemagician, “and no one can think of what to do with them. So we just keep digging them up and throwing them out. Now,” he said, taking a silver whistle from his pocket and blowing it loudly, “let’s have some lunch.”

And for the first time in his life the astonished bug couldn’t think of a thing to say.

Into the cavern rushed eight of the strongest miners carrying an immense caldron which bubbled and sizzled and sent great clouds of savory steam spiraling slowly to the ceiling. A sweet yet pungent aroma hung in the air and drifted easily from one anxious nose to the other, stopping only long enough to make several mouths water and a few stomachs growl. Milo, Tock, and the Humbug watched eagerly as the rest of the workers put down their tools and gathered around the big pot to help themselves.

“Perhaps you’d care for something to eat?” said the Mathemagician, offering each of them a heaping bowlful.

“Yes, sir,” said Milo, who was beside himself with hunger.

“Thank you,” added Tock.

The Humbug made no reply, for he was already too busy eating, and in a moment the three of them had finished absolutely everything they’d been given.

“Please have another portion,” said the Mathemagician, filling their bowls once more; and as quickly as they’d finished the first one the second was emptied too “Don’t stop now,” he insisted, serving them again,

and again,

and again,

and again,

and again.

“How very strange,” thought Milo as he finished his seventh helping. “Each one I eat makes me a little hungrier than the one before.

“Do have some more,” suggested the Mathemagician, and they continued to eat just as fast as he filled the plates.

After Milo had eaten nine portions, Tock eleven, and the Humbug, without once stopping to look up, twenty-three, the Mathemagician blew his whistle for a second time and immediately the pot was removed and the miners returned to work.

“U-g-g-g-h-h-h,” gasped the bug, suddenly realizing that he was twenty-three times hungrier than when he started, “I think I’m starving.”

“Me, too,” complained Milo, whose stomach felt as empty as he could ever remember; “and I ate so much.”

“Yes, it was delicious, wasn’t it?” agreed the pleased Dodecahedron, wiping the gravy from several of his mouths. “It’s the specialty of the kingdom – subtraction stew.”

“I have more of an appetite than when I began,” said Tock, leaning weakly against one of the larger rocks.

“Certainly,” replied the Mathemagician; “what did you expect? The more you eat, the hungrier you get. Everyone knows that.”

“They do?” said Milo doubtfully. “Then how do you ever get enough?”

“Enough?” he said impatiently. “Here in Digitopolis we have our meals when we’re full and eat until we’re hungry. That way, when you don’t have anything at all, you have more than enough. It’s a very economical system. You must have been quite stuffed to have eaten so much.”

“It’s completely logical,” explained the Dodecahedron. “The more you want, the less you get, and the less you get, the more you have. Simple arithmetic, that’s all. Suppose you had something and added something to it. What would that make?”

“More,” said Milo quickly.

“Quite correct,” he nodded. “Now suppose you had something and added nothing to it. What would you have?”

“The same,” he answered again, without much conviction.

“Splendid,” cried the Dodecahedron. “And suppose you had something and added less than nothing to it. What would you have then?”

“FAMINE!” roared the anguished Humbug, who suddenly realized that that was exactly what he’d eaten twenty-three bowls of.

“It’s not as bad as all that,” said the Dodecahedron from his most sympathetic face. “In a few hours you’ll be nice and full again – just in time for dinner.”

“Oh dear,” said Milo sadly and softly. “I only eat when I’m hungry.”

“What a curious idea,” said the Mathemagician, raising his staff over his head and scrubbing the rubber end back and forth several times on the ceiling. “The next thing you’ll have us believe is that you only sleep when you’re tired.” And by the time he’d finished the sentence, the cavern, the miners, and the Dodecahedron had vanished, leaving just the four of them standing in the Mathemagician’s workshop.

“I often find,” he casually explained to his dazed visitors, “that the best way to get from one place to another is to erase everything and begin again. Please make yourself at home.”

“Do you always travel that way?” asked Milo as he glanced curiously at the strange circular room, whose sixteen tiny arched windows corresponded exactly to the sixteen points of the compass. Around the entire circumference were numbers from zero to three hundred and sixty, marking the degrees of the circle, and on the floor, walls, tables, chairs, desks, cabinets, and ceiling were labels showing their heights, widths, depths, and distances to and from each other. To one side was a gigantic note pad set on an artist’s easel, and from hooks and strings hung a collection of scales, rulers, measures, weights, tapes, and all sorts of other devices for measuring any number of things in every possible way.

“No indeed,” replied the Mathemagician, and this time he raised the sharpened end of his staff, drew a thin straight line in the air, and then walked gracefully across it from one side of the room to the other. “Most of the time I take the shortest distance between any two points. And, of course, when I should be in several places at once,” he remarked, writing 7 X 1 = 7 carefully on the note pad, “I simply multiply.”

Suddenly there were seven Mathemagicians standing side by side, and each one looked exactly like the other.

“How did you do that?” gasped Milo.

“There’s nothing to it,” they all said in chorus, “if you have a magic staff.” Then six of them canceled themselves out and simply disappeared.

“But it’s only a big pencil,” the Humbug objected, tapping at it with his cane.

“True enough,” agreed the Mathemagician; “but once you learn to use it, there’s no end to what you can do.”

“Can you make things disappear?” asked Milo excitedly.

“Why, certainly,” he said, striding over to the easel. “Just step a little closer and watch carefully.”

After demonstrating that there was nothing up his sleeves, in his hat, or behind his back, he wrote quickly:

4 + 9 – 2 x 16 + 1 / 3 x 6 – 67 + 8 x 2 – 3 + 26 – 1 / 34 + 3 / 7 + 2 – 5 =

Then he looked up expectantly.

“Seventeen!” shouted the bug, who always managed to be first with the wrong answer.

“It all comes to zero,” corrected Milo.

“Precisely,” said the Mathemagician, making a very theatrical bow, and the entire line of numbers vanished before their eyes. “Now is there anything else you’d like to see?”

“Yes, please,” said Milo. “Can you show me the biggest number there is?”

“I’d be delighted,” he replied, opening one of the closet doors. “We keep it right here. It took four miners just to dig it out.”

Inside was the biggest  Milo had ever seen. It was fully twice as high as the Mathemagician.

Milo had ever seen. It was fully twice as high as the Mathemagician.

“No, that’s not what I mean,” objected Milo. “Can you show me the longest number there is?” “Surely,” said the Mathemagician, opening another door. “Here it is. It took three carts to carry it here.”

Inside this closet was the longest  imaginable. It was just about as wide as the three was high.

imaginable. It was just about as wide as the three was high.

“No, no, no, that’s not what I mean either,” he said, looking helplessly at Tock.

“I think what you would like to see,” said the dog, scratching himself just under half-past four, “is the number of greatest possible magnitude.”

“Well, why didn’t you say so?” said the Mathemagician, who was busily measuring the edge of a raindrop. “What’s the greatest number you can think of?”

“Nine trillion, nine hundred ninety-nine billion, nine hundred ninety-nine million, nine hundred ninety-nine thousand, nine hundred ninety-nine,” recited Milo breathlessly.

“Very good,” said the Mathemagician. “Now add one to it. Now add one again,” he repeated when Milo had added the previous one. “Now add one again. Now add one again. Now add one again. Now add one again. Now add one again. Now add one again. Now add…”

“But when can I stop?” pleaded Milo.

“Never,” said the Mathemagician with a little smile, “for the number you want is always at least one more than the number you’ve got, and it’s so large that if you started saying it yesterday you wouldn’t finish tomorrow.”

“Where could you ever find a number so big?” scoffed the Humbug.

“In the same place they have the smallest number there is,” he answered helpfully; “and you know what that is.”

“Certainly,” said the bug, suddenly remembering something to do at the other end of the room.

“One one-millionth?” asked Milo, trying to think of the smallest fraction possible.

“Almost,” said the Mathemagician. “Now divide it in half. Now divide it in half again. Now divide it in half again. Now divide it in half again. Now divide it in half again. Now divide it in half again. Now divide…”

“Oh dear,” shouted Milo, holding his hands to his ears, “doesn’t that ever stop either?”

“How can it,” said the Mathemagician, “when you can always take half of whatever you have left until it’s so small that if you started to say it right now you’d finish even before you began?”

“Where could you keep anything so tiny?” Milo asked, trying very hard to imagine such a thing.

The Mathemagician stopped what he was doing and explained simply, “Why, in a box that’s so small you can’t see it and that’s kept in a drawer that’s so small you can’t see it, in a dresser that’s so small you can’t see it, in a house that’s so small you can’t see it, on a street that’s so small you can’t see it, in a city that’s so small you can’t see it, which is part of a country that’s so small you can’t see it, in a world that’s so small you can’t see it.”

Then he sat down, fanned himself with a handkerchief, and continued. “Then, of course, we keep the whole thing in another box that’s so small you can’t see it – and, if you follow me, I’ll show you where to find it.”

They walked to one of the small windows and there, tied to the sill, was one end of a line that stretched along the ground and into the distance until completely out of sight.

“Just follow that line forever,” said the Mathemagician, “and when you reach the end, turn left. There you’ll find the land of Infinity, where the tallest, the shortest, the biggest, the smallest, and the most and the least of everything are kept.”

“I really don’t have that much time,” said Milo anxiously. “Isn’t there a quicker way?”

“Well, you might try this flight of stairs,” he suggested, opening another door and pointing up. “It goes there, too.”

Milo bounded across the room and started up the stairs two at a time. “Wait for me, please,” he shouted to Tock and the Humbug. “I’ll be gone just a few minutes.

Up he went – very quickly at first – then more slowly – then in a little while even more slowly than that – and finally, after many minutes of climbing up the endless stairway, one weary foot was barely able to follow the other. Milo suddenly realized that with all his effort he was no closer to the top than when he began, and not a great deal further from the bottom. But he struggled on for a while longer, until at last, completely exhausted, he collapsed onto one of the steps.

“I should have known it,” he mumbled, resting his tired legs and filling his lungs with air. “This is just like the line that goes on forever, and I’ll never get there.”

“You wouldn’t like it much anyway,” someone replied gently. “Infinity is a dreadfully poor place. They can never manage to make ends meet.”

Milo looked up, with his head still resting heavily in his hand; he was becoming quite accustomed to being addressed at the oddest times, in the oddest places, by the oddest people – and this time he was not at all disappointed. Standing next to him on the step was exactly one half of a small child who had been divided neatly from top to bottom.

“Pardon me for staring,” said Milo, after he had been staring for some time, “but I’ve never seen half a child before.”

“It’s .58 to be precise,” replied the child from the left side of his mouth (which happened to be the only side of his mouth).

“I beg your pardon?” said Milo.

“It’s .58,” he repeated; “it’s a little bit more than a half.”

“Have you always been that way?” asked Milo impatiently, for he felt that that was a needlessly fine distinction.

“My goodness, no,” the child assured him. “A few years ago I was just .42 and, believe me, that was terribly inconvenient.”

“What is the rest of your family like?” said Milo, this time a bit more sympathetically.

“Oh, we’re just the average family,” he said thoughtfully; “mother, father, and 2.58 children – and, as I explained, I’m the .58.”

“It must be rather odd being only part of a person,” Milo remarked.

“Not at all,” said the child. “Every average family has 2.58 children, so I always have someone to play with. Besides, each family also has an average of 1.3 automobiles, and since I’m the only one who can drive three tenths of a car, I get to use it all the time.”

“But averages aren’t real,” objected Milo; “they’re just imaginary.”

“That may be so,” he agreed, “but they’re also very useful at times. For instance, if you didn’t have any money at all, but you happened to be with four other people who had ten dollars apiece, then you’d each have an average of eight dollars. Isn’t that right?”

“I guess so,” said Milo weakly.

“Well, think how much better off you’d be, just because of averages,” he explained convincingly. “And think of the poor farmer when it doesn’t rain all year: if there wasn’t an average yearly rainfall of 37 inches in this part of the country, all his crops would wither and die.”

It all sounded terribly confusing to Milo, for he had always had trouble in school with just this subject.

“There are still other advantages,” continued the child. “For instance, if one rat were cornered by nine cats, then, on the average, each cat would be 10 per cent rat and the rat would be 90 per cent cat. If you happened to be a rat, you can see how much nicer it would make things.”

“But that can never be,” said Milo, jumping to his feet.

“Don’t be too sure,” said the child patiently, “for one of the nicest things about mathematics, or anything else you might care to learn, is that many of the things which can never be, often are. You see,” he went on, “it’s very much like your trying to reach Infinity. You know that it’s there, but you just don’t know where – but just because you can never reach it doesn’t mean that it’s not worth looking for.”

“I hadn’t thought of it that way,” said Milo, starting down the stairs. “I think I’ll go back now.”

“A wise decision,” the child agreed; “but try again someday – perhaps you’ll get much closer.” And, as Milo waved good-by, he smiled warmly, which he usually did on the average of 47 times a day.

“Everyone here knows so much more than I do,” thought Milo, as he leaped from step to step. “I’ll have to do a lot better if I’m going to rescue the princesses.”

In a few moments he’d reached the bottom again and burst into the workshop, where Tock and the Humbug were eagerly watching the Mathemagician perform.

“Ah, back already,” he cried, greeting him with a friendly wave. “I hope you found what you were looking for.”

“I’m afraid not,” admitted Milo. And then he added in a very discouraged tone, “Everything in Digitopolis is much too difficult for me.”

The Mathemagician nodded knowingly and stroked his chin several times. “You’ll find,” he remarked gently, “that the only thing you can do easily is be wrong, and that’s hardly worth the effort.”

Milo tried very hard to understand all the things he’d been told, and all the things he’d seen, and, as he spoke, one curious thing still bothered him.

“Why is it,” he said quietly, “that quite often even the things which are correct just don’t seem to be right?”

A look of deep melancholy crossed the Mathemagician’s face and his eyes grew moist with sadness. Everything was silent, and it was several minutes before he was able to reply at all.

“How very true,” he sobbed, supporting himself on the staff. “It has been that way since Rhyme and Reason were banished.”

“Quite so,” began the Humbug. “I personally feel that…”

“AND ALL BECAUSE OF THAT STUBBORN WRETCH AZAZ,” roared the Mathemagician, completely overwhelming the bug, for now his sadness had changed to fury and he stalked about the room adding up anger and multiplying wrath. “IT’S ALL HIS FAULT.”

“Perhaps if you discussed it with him “ Milo started to say, but never had time to finish.

“He’s much too unreasonable,” interrupted the Mathemagician again. “Why, just last month I sent him a very friendly letter, which he never had the courtesy to answer. See for yourself.”

He handed Milo a copy of the letter, which read:

“But maybe he doesn’t understand numbers,” said Milo, who found it a little difficult to read himself.

“NONSENSE!” he bellowed. “Everyone understands numbers. No matter what language you speak, they always mean the same thing. A seven is a seven anywhere in the world.”

“My goodness,” thought Milo, “everybody is so terribly sensitive about the things they know best.”

“With your permission,” said Tock, changing the subject, “we’d like to rescue Rhyme and Reason.”

“Has Azaz agreed to it?” the Mathemagician inquired.

“Yes, sir,” the dog assured him.

“THEN I DON’T,” he thundered again, “for since they’ve been banished, we’ve never agreed on anything – and we never will.” He emphasized his last remark with a dark and ominous look.

“Never?” asked Milo, with the slightest touch of disbelief in his voice.

“NEVER!” he repeated. “And if you can prove otherwise, you have my permission to go.”

“Well,” said Milo, who had thought about this problem very carefully ever since leaving Dictionopolis. “Then with whatever Azaz agrees, you disagree.”

“Correct,” said the Mathemagician with a tolerant smile.

“And with whatever Azaz disagrees, you agree.”

“Also correct,” yawned the Mathemagician, nonchalantly cleaning his fingernails with the point of his staff.

“Then each of you agrees that he will disagree with whatever each of you agrees with,” said Milo triumphantly; “and if you both disagree with the same thing, then aren’t you really in agreement?”

“I’VE BEEN TRICKED!” cried the Mathemagician helplessly, for no matter how he figured, it still came out just that way.

“Splendid effort,” commented the Humbug jovially; “exactly the way I would have done it myself.”

“And now may we go?” added Tock.

The Mathemagician accepted his defeat with grace, nodded weakly, and then drew the three travelers to his side.

“It’s a long and dangerous journey,” he began softly, and a furrow of concern creased his forehead. “Long before you find them, the demons will know you’re there. Watch for them well,” he emphasized, “for when they appear, it might be too late.”

The Humbug shuddered down to his shoes, and Milo felt the tips of his fingers suddenly grow cold.

“But there is one problem even more serious than that,” he whispered ominously.

“What is it?” gasped Milo, who was not sure he really wanted to know.

“I’m afraid I can tell you only when you return. Come along,” said the Mathemagician, “and I’ll show you the way.”

And, simply by carrying the three, he transported them all to the very edge of Digitopolis. Behind them lay all the kingdoms of Wisdom, and up ahead a narrow rutted path led toward the mountains and darkness.

“We’ll never get the car up that,” said Milo unhappily.

“True enough,” replied the Mathemagician, “but you can be in Ignorance quick enough without riding all the way; and if you’re to be successful, it will have to be step by step.”

“But I would like to take my gifts,” he insisted.

“So you shall,” announced the Dodecahedron, who appeared from nowhere with his arms full.

“Here are your sights, here are your sounds, and here,” he said, handing Milo the last of them disdainfully, “are your words.”

“And, most important of all,” added the Mathemagician, “here is your own magic staff. Use it well and there is nothing it cannot do for you.”

He placed in Milo’s breast pocket a small gleaming pencil which, except for the size, was much like his own. Then, with a last word of encouragement, he and the Dodecahedron (who was simultaneously sobbing, frowning, pining, and sighing from four of his saddest faces) made their farewells and watched as the three tiny figures disappeared into the forbidding mountains of Ignorance.

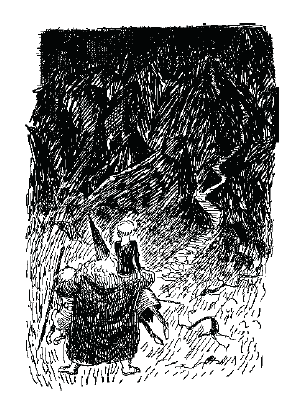

Almost immediately the light began to fade as the difficult path wandered aimlessly upward, inching forward almost as reluctantly as the trembling Humbug. Tock as usual led the way, sniffing ahead for danger, and Milo, his bag of precious possessions slung over one shoulder, followed silently and resolutely behind.

“Perhaps someone should stay back to guard the way,” said the unhappy bug, offering his services; but, since his suggestion was met with silence, he followed glumly along.

The higher they went, the darker it became, though it wasn’t the darkness of night, but rather more like a mixture of lurking shadows and evil intentions which oozed from the slimy moss-covered cliffs and blotted out the light. A cruel wind shrieked through the rocks and the air was thick and heavy, as if it had been used several times before.

On they went, higher and higher up the dizzying trail, on one side the sheer stone walls and brutal peaks towering above them, and on the other an endless, limitless, bottomless nothing.

“I can hardly see a thing,” said Milo, taking hold of Tock’s tail as a sticky mist engulfed the moon. “Perhaps we should wait until morning.”

“They’ll be mourning for you soon enough,” came a reply from directly above, and this was followed by a hideous cackling laugh very much like someone choking on a fishbone.

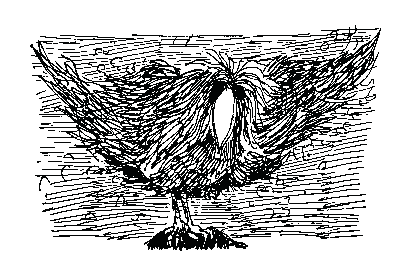

Clinging to one of the greasy rocks and blending almost perfectly with it was a large, unkempt, and exceedingly soiled bird who looked more like a dirty floor mop than anything else. He had a sharp, dangerous beak, and the one eye he chose to open stared down maliciously.

“I don’t think you understand,” said Milo timidly as the watchdog growled a warning. “We’re looking for a place to spend the night.”

“It’s not yours to spend,” the bird shrieked again, and followed it with the same horrible laugh.

“That doesn’t make any sense, you see – ” he started to explain.

“Dollars or cents, it’s still not yours to spend,” the bird replied haughtily.

“But I didn’t mean...” insisted Milo.

“Of course you’re mean,” interrupted the bird, closing the eye that had been open and opening the one that had been closed. “Anyone who’d spend a night that doesn’t belong to him is very mean.”

“Well, I thought that by...” he tried again desperately.

“That’s a different story,” interjected the bird a bit more amiably. “If you want to buy, I’m sure I can arrange to sell, but with what you’re doing you’ll probably end up in a cell anyway.”

“That doesn’t seem right,” said Milo helplessly, for, with the bird taking everything the wrong way, he hardly knew what he was saying.

“Agreed,” said the bird, with a sharp click of his beak, “but neither is it left, although if I were you I would have left a long time ago.”

“Let me try once more,” he said in an effort to explain. “In other words...”

“You mean you have other words?” cried the bird happily. “Well, by all means, use them. You’re certainly not doing very well with the ones you have now.”

“Must you always interrupt like that?” said Tock irritably, for even he was becoming impatient.

“Naturally,” he cackled; “it’s my job. I take the words right out of your mouth. Haven’t we met before? I’m the Everpresent Wordsnatcher, and I’m sure I know your friend the bug.” And then he leaned all the way forward and gave a terrible knowing smile.

The Humbug, who was too big to hide and too frightened to move, denied everything.

“Is everyone who lives in Ignorance like you?” asked Milo.

“Much worse,” he said longingly. “But I don’t live here. I’m from a place very far away called Context.”

“Don’t you think you should be getting back?” suggested the bug, holding one arm up in front of him.

“What a horrible thought.” The bird shuddered. “It’s such an unpleasant place that I spend almost all my time out of it. Besides, what could be nicer than these grimy mountains?”

“Almost anything,” thought Milo as he pulled his collar up. And then he asked the bird, “Are you a demon?”

“I’m afraid not,” he replied sadly, as several filthy tears rolled down his beak. “I’ve tried, but the best I can manage to be is a nuisance,” and, before Milo could reply, he flapped his dingy wings and flew off in a cascade of dust and dirt and fuzz.

“Wait!” shouted Milo, who’d thought of many more questions he wanted to ask.

“Thirty-four pounds,” shrieked the bird as he disappeared into the fog.

“He was certainly no help,” said Milo after they had been walking again for some time.

“That’s why I drove him off,” cried the Humbug, fiercely brandishing his cane. “Now let’s find the demons.”

“That might be sooner than you think,” remarked Tock, looking back at the suddenly trembling bug; and the trail turned again and continued to climb.

In a few minutes they’d reached the crest, only to find that beyond it lay another one even higher, and beyond that several more, whose tops were lost in the swirling darkness. For a short stretch the path became broad and flat, and just ahead, leaning comfortably against a dead tree, stood a very elegant-looking gentleman. He was beautifully dressed in a dark suit with a wellpressed shirt and tie. His shoes were polished, his nails were clean, his hat was well brushed, and a white handkerchief adorned his breast pocket. But his expression was somewhat blank. In fact, it was completely blank, for he had neither eyes, nose, nor mouth. “Hello, little boy,” he said, amiably shaking Milo by the hand. “And how’s the faithful dog?” he inquired, giving Tock three or four strong and friendly pats. “And who is this handsome creature?” he asked, tipping his hat to the very pleased Humbug. “I’m so happy to see you all.”

“What a pleasant surprise to meet someone so nice,” they all thought, “and especially here.”

“I wonder if you could spare me a little of your time,” he inquired politely, “and help with a few small jobs?”

“Why, of course,” said the Humbug cheerfully.

“Gladly,” added Tock.

“Yes, indeed,” said Milo, who wondered for just a moment how it was possible for someone so agreeable to have a face with no features at all.

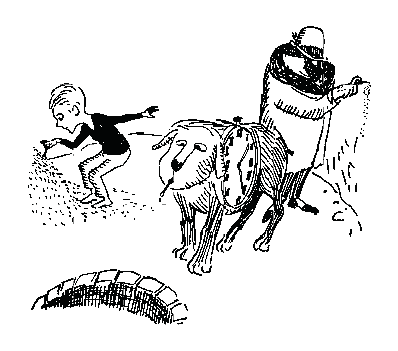

“Splendid,” he said happily, “for there are just three tasks. Firstly, I would like to move this pile from here to there,” he explained, pointing to an enormous mound of fine sand; “but I’m afraid that all I have is this tiny tweezers.” And he gave them to Milo, who immediately began transporting one grain at a time.

“Secondly, I would like to empty this well and fill the other; but I have no bucket, so you’ll have to use this eye dropper.” And he handed it to Tock, who undertook at once to carry one drop at a time from well to well.

“And, lastly, I must have a hole through this cliff, and here is a needle to dig it.” The eager Humbug quickly set to work picking at the solid granite wall.

When they had all been safely started, the very pleasant man returned to the tree and, leaning against it once more, continued to stare vacantly down the trail, while Milo, Tock, and the Humbug worked hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour after hour